1. Introduction

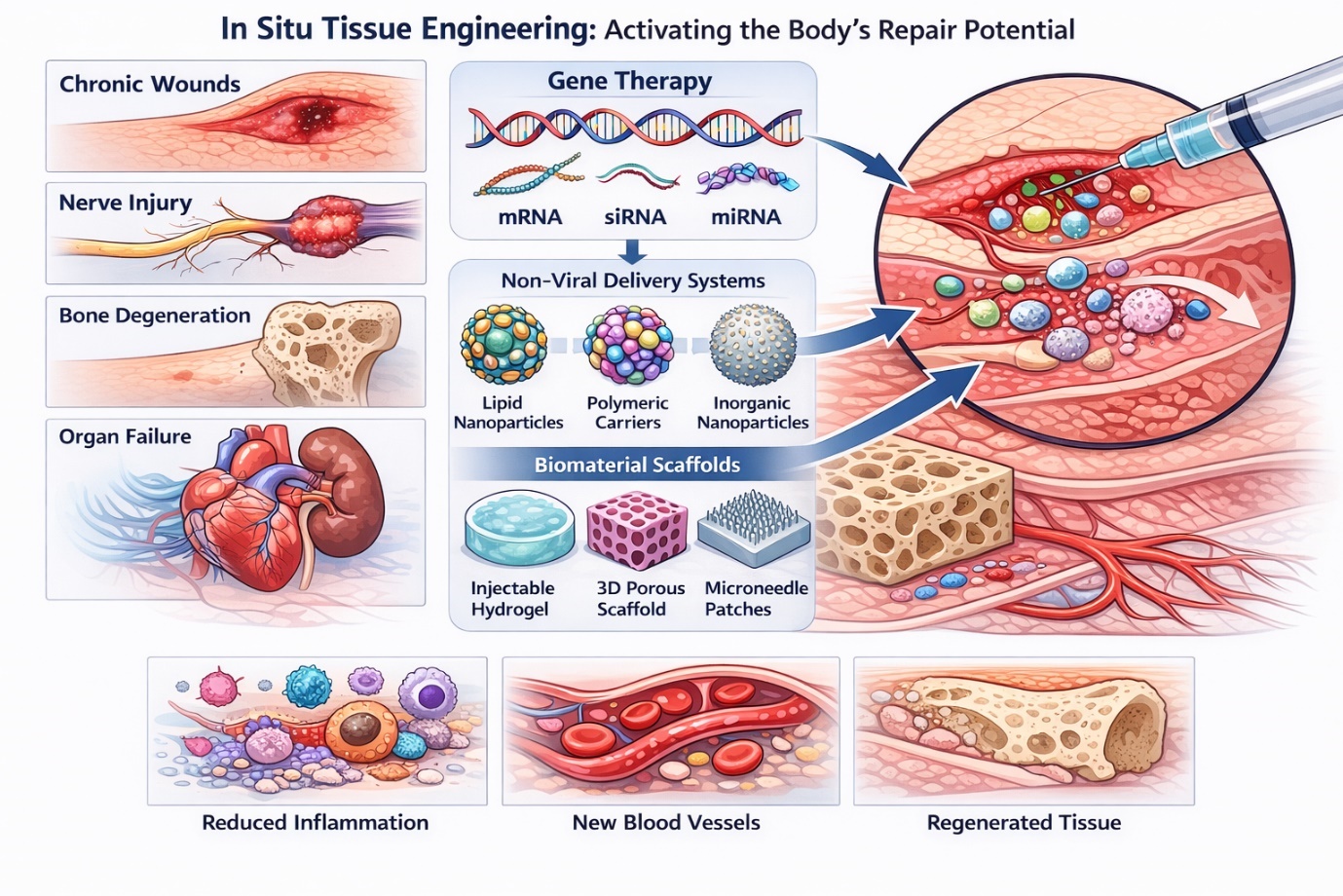

Regenerative medicine has steadily shifted from an aspirational concept toward a practical framework for addressing tissue damage that cannot be resolved through conventional clinical interventions. Chronic wounds, degenerative musculoskeletal disorders, nerve injuries, and organ failure frequently overwhelm the body’s intrinsic repair capacity, leaving limited therapeutic options. In this context, in situ tissue engineering has emerged as a compelling strategy—not by replacing damaged tissue outright, but by activating endogenous repair mechanisms directly at the site of injury. Rather than introducing fully formed tissues or large numbers of exogenous cells, this approach seeks to guide cellular behavior where regeneration is needed most (Malek-Khatabi et al., 2020; Moncal et al., 2022).

At the heart of this strategy lies gene regulation. Delivering nucleic acids such as plasmid DNA, small interfering RNA (siRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and messenger RNA enables intervention upstream of protein synthesis, influencing cellular fate, inflammatory responses, angiogenesis, and matrix remodeling. Conceptually, this represents a powerful shift: if gene expression can be modulated with sufficient spatial and temporal precision, tissue repair can be steered rather than forced. The clinical emergence of RNA interference–based therapeutics has reinforced this idea, demonstrating that nucleic acid modulation can achieve durable biological effects when appropriately delivered (Adams et al., 2018; Elbashir et al., 2001; Ding et al., 2019). Yet translating this promise into reliable regenerative outcomes has proven far from straightforward.

One of the earliest and most persistent obstacles is the intrinsic fragility of nucleic acids. In physiological environments, they are rapidly degraded by nucleases, exhibit poor cellular uptake due to size and charge constraints, and are prone to nonspecific biodistribution. Even when internalization occurs, endosomal entrapment and unintended immune activation frequently limit therapeutic efficacy. These challenges are not merely technical inconveniences; they fundamentally shape the feasibility of gene-based regenerative therapies and dictate delivery system design (Castanotto & Rossi, 2009; Motamedi et al., 2024). As a result, the success of in situ tissue engineering depends less on the nucleic acids themselves than on how effectively they are delivered.

Delivery strategies are commonly divided into viral and non-viral systems, each offering distinct advantages and liabilities. Viral vectors—including adenoviruses, adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), and lentiviruses—benefit from evolutionary refinement, enabling efficient gene transfer and sustained expression. In regenerative contexts, viral systems have demonstrated robust outcomes in neural tissue repair, skeletal muscle regeneration, and spinal cord injury models (Chandler et al., 2000; Finkel et al., 2024). However, this efficiency comes at a cost. Immunogenicity, insertional mutagenesis, limited cargo capacity, and manufacturing complexity continue to constrain broader application, particularly in settings requiring localized or repeat dosing (Bulcha et al., 2021).

These limitations have gradually redirected attention toward non-viral delivery systems. Once viewed as inherently less efficient, non-viral vectors have advanced rapidly alongside developments in nanotechnology and biomaterials. Lipid-based nanoparticles, polymeric carriers, inorganic nanoparticles, and biomimetic systems now offer a degree of tunability that viral platforms cannot easily achieve. Rather than relying on a single mechanism of entry, these systems can be engineered to simultaneously protect nucleic acids, enhance cellular uptake, promote endosomal escape, and enable localized delivery (McCarthy et al., 2014; Bae et al., 2016).

Among non-viral platforms, lipid nanoparticles stand out due to their growing clinical maturity. Their modular composition allows precise control over stability, biodistribution, and release kinetics, making them attractive for regenerative applications requiring transient yet potent gene modulation (Chen, et al., 2022). Polymeric systems offer complementary advantages, with subtle changes in architecture dramatically influencing charge density, degradation behavior, and cytocompatibility (Bae et al., 2016). Inorganic nanoparticles contribute additional functionality, such as high surface area and mechanical robustness, though their long-term biodegradation and clearance remain under investigation (Lei et al., 2019; Liu, et al., 2021a). Biomimetic carriers, including engineered exosomes and microbial vectors, introduce further sophistication by leveraging endogenous communication pathways to improve delivery efficiency and immune tolerance (Liu, et al., 2021a; Chen, Li, et al., 2022).

Yet delivery vectors alone are rarely sufficient in regenerative contexts. Tissue repair is inherently localized, dynamic, and mechanically regulated. This realization has driven increasing integration of gene delivery systems within biomaterial scaffolds. Rather than serving solely as passive carriers, scaffolds create microenvironments that influence cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation while simultaneously controlling the release of genetic cargo. Injectable hydrogels, in particular, have gained prominence due to their minimally invasive application and ability to conform to irregular defects. Their tunable crosslinking and degradation properties enable sustained gene release aligned with critical phases of tissue healing (Feng et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2023).

Three-dimensional porous scaffolds extend this concept by providing structural cues reminiscent of the extracellular matrix. When combined with non-viral gene carriers, these constructs have demonstrated enhanced angiogenesis, bone regeneration, and neural repair in preclinical models (Guo et al., 2010; Acri et al., 2021). Sheet-like systems, including layered films and microneedle arrays, address a different set of clinical needs, enabling superficial and sustained gene delivery for skin repair and wound healing (Castleberry et al., 2016a; Qu et al., 2020). Each platform reflects a balance between biological ambition and practical constraint.

Despite encouraging progress, translation to clinical practice remains uneven. Mechanical limitations restrict the use of certain hydrogels in load-bearing tissues, while light-responsive systems face challenges related to tissue penetration depth (Huynh et al., 2016; Castleberry et al., 2016b). Manufacturing scalability, sterilization, and regulatory approval introduce additional layers of complexity that are often underappreciated in early-stage studies. Moreover, long-term safety—particularly concerning nanoparticle persistence and immune modulation—continues to demand careful evaluation.

Taken together, the literature reveals both substantial advancement and persistent fragmentation. Individual studies frequently demonstrate success within narrowly defined models, yet comparative effectiveness across delivery systems and scaffold platforms remains difficult to discern. This underscores the need for systematic synthesis. By integrating evidence across materials, delivery strategies, and tissue targets, these reviews can clarify which design principles consistently drive regenerative outcomes and which remain context-dependent. Such analyses are essential not only for guiding future research but also for advancing gene-activated biomaterials toward clinical reality.