1. Introduction

Bangladesh, a country blessed with lush landscapes and rich biodiversity, is home to an extraordinary variety of indigenous medicinal plants. For centuries, these plants have played a central role in traditional healthcare practices, particularly in rural communities where access to modern medical facilities is often limited. Far from being simply remnants of the past, these traditional remedies represent living systems of knowledge that continue to guide daily healthcare decisions for millions of people. Beyond cultural heritage, these plants carry untapped scientific promise, offering bioactive compounds that may lead to novel therapeutics in the modern pharmaceutical world (Faruque et al., 2018; Ahmad et al., 2016; Bilal et al., 2016).

The use of indigenous medicinal plants in Bangladesh is deeply interwoven with cultural practices and local traditions. Folk healers, often referred to as kabiraj or traditional practitioners, rely heavily on plants for the treatment of a broad range of health conditions, from digestive issues and infections to chronic inflammatory disorders. These healers not only provide remedies but also act as custodians of ethnobotanical knowledge, safeguarding centuries of empirical wisdom. For instance, communities living along the Ghaghut, Bengali, and Padma rivers have been documented as possessing extensive ethnomedicinal knowledge, passing down practices orally across generations (Faruque et al., 2018; Dirir et al., 2017). Such practices reveal a profound and practical understanding of the local flora, positioning traditional medicine as a valuable complement to modern healthcare systems.

Scientific exploration of these plants highlights their rich phytochemical diversity. Many species are endowed with alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, glycosides, and saponins—compounds known for their therapeutic roles. These phytochemicals are not mere chemical curiosities; they form the basis for pharmacological activities such as antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and even anticancer effects. For example, flavonoids are celebrated for their ability to neutralize oxidative stress and mitigate inflammation, while saponins are widely recognized for antimicrobial properties (Akhtar, 2022; Grochowski et al., 2019; Kähkönen et al., 1999). These findings lend scientific credibility to traditional claims, bridging the gap between ancient wisdom and modern validation.

One of the most pressing health concerns in Bangladesh is the persistent burden of infectious diseases. Rural populations, in particular, face heightened vulnerability due to limited access to antibiotics and rising concerns about antimicrobial resistance. Medicinal plants present a promising avenue for addressing these challenges. Several studies have demonstrated that extracts from Bangladeshi plants show notable antimicrobial activity against a spectrum of pathogens (Siddique et al., 2021; Gemeda et al., 2018; Pawar & Khan, 2007). Such discoveries are timely, given the global urgency to discover alternatives in the face of antibiotic resistance.

The antimicrobial effects of these plants often stem from their ability to disrupt vital microbial processes. Phytochemicals can interfere with cell wall synthesis, impair protein production, and destabilize microbial membranes, making them highly versatile defense tools (Kadir et al., 2012; Khurm et al., 2016). This pharmacological potential suggests that Bangladeshi medicinal plants should not be viewed merely as adjuncts to conventional medicine but rather as strong candidates for the development of entirely new classes of therapeutic agents.

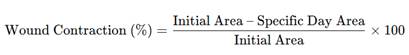

In addition to fighting infections, Bangladeshi medicinal plants have long been valued for their wound-healing properties. Traditional healers frequently apply plant extracts, pastes, or poultices to cuts, burns, and chronic sores, and such practices are now being validated by scientific research (Sidhu et al., 1999; Varoglu et al., 2010; Murthy et al., 2013; Permata et al., 2024). Phytochemicals like flavonoids and tannins have been shown to promote tissue regeneration, reduce inflammation, and accelerate the closure of wounds (Sairam et al., 2001; Sharath et al., 2010). For instance, Bacopa monnieri has demonstrated significant wound-healing activity in animal models, improving both wound contraction and epithelialization time (Murthy et al., 2013; Sairam et al., 2001). Similarly, Calotropis gigantea, traditionally used for treating skin ailments, has been reported to enhance wound repair through mechanisms involving anti-inflammatory action and collagen synthesis (Permata et al., 2024; Argal & Pathak, 2006). These findings not only validate indigenous practices but also highlight the importance of preserving traditional knowledge as a reservoir of biomedical innovation.

Importantly, the integration of herbal medicine into modern healthcare is no longer seen as optional but rather as essential. The World Health Organization has long advocated for recognizing traditional medicine as part of national healthcare strategies, particularly in countries like Bangladesh where plant-based remedies remain widely used. However, successful integration requires careful balancing of cultural respect with scientific rigor. Traditional remedies must undergo stringent pharmacological evaluation to ensure efficacy and safety before they can be formally adopted into mainstream medicine (Nahar et al., 2024; Anders et al., 2010).

The study of indigenous medicinal plants is not only about discovering new drugs but also about honoring cultural heritage and addressing unmet health needs. In Bangladesh, the reliance on medicinal plants is both a matter of tradition and necessity, particularly in remote areas where conventional healthcare may be scarce. As scientific evidence continues to mount, it becomes increasingly clear that these plants represent a vital bridge between the wisdom of the past and the innovations of the future. Exploring their therapeutic potential aligns with global health priorities, particularly in the fight against infectious diseases, chronic inflammation, and wound management (Bilal et al., 2016; Gemeda et al., 2018).

Therefore, the present study seeks to evaluate the wound-healing efficacy of methanolic extracts from selected indigenous plants of Bangladesh using in vivo excision wound models. By focusing on Alpinia nigra, Bacopa monnieri, Calotropis gigantea, and Cynodon dactylon, this research not only tests traditional claims under controlled conditions but also contributes to the growing body of scientific evidence supporting the pharmacological importance of Bangladeshi flora (Annapurna et al., 2013; Dande & Khan, 2012). Ultimately, such efforts may pave the way for developing affordable, accessible, and culturally relevant medicines, bringing together the best of tradition and science.