1. Introduction

The modern history of medicine is inseparable from antibiotics. For decades, they have underwritten the safety of surgery, chemotherapy, transplantation, and even routine clinical care. Yet that foundation is no longer secure. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has accelerated across clinical and environmental settings, reshaping once-manageable infections into persistent therapeutic challenges. Gram-negative bacteria, in particular, have demonstrated formidable intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms, limiting the utility of many frontline drugs (Breijyeh et al., 2020; Silver, 2011). The urgency of this problem has prompted global prioritization efforts, including formal identification of critical resistant pathogens requiring immediate research attention (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017; Mulani et al., 2019).

The roots of the current crisis are complex. Bacteria evolve rapidly through mutation and horizontal gene transfer, redistributing resistance determinants across species and ecological boundaries. Environmental systems now act as reservoirs of resistance genes, especially in marine contexts where anthropogenic pressures intersect with microbial diversity (Hatosy & Martiny, 2015; Rojas et al., 2020). Clinical overuse, agricultural application, and inadequate stewardship amplify selective pressures, allowing resistant populations to dominate. What once appeared to be isolated hospital-based phenomena now reflects a deeply interconnected ecological issue.

Historically, antibiotic discovery flourished during the mid-twentieth century. Natural products—particularly those derived from soil-dwelling actinomycetes—yielded transformative therapeutics (Newman et al., 2003; Robertsen & Musiol-Kroll, 2019). This “golden age” established the structural and mechanistic foundations of modern antimicrobial therapy. Yet momentum waned in subsequent decades. The pipeline narrowed as rediscovery rates increased, research costs escalated, and pharmaceutical investment declined (Payne et al., 2007; Brown & Wright, 2016). The stagnation was not merely financial; it was conceptual. Traditional screening strategies repeatedly recovered known scaffolds, revealing diminishing returns from conventional approaches (Donadio et al., 2010).

Compounding this slowdown was a technical limitation that, in retrospect, seems almost paradoxical: the vast majority of microbes in nature could not be cultured under laboratory conditions. Early recognition of this “uncultivable” majority highlighted a profound blind spot in microbial exploration (Kaeberlein et al., 2002). Subsequent innovations such as in situ cultivation technologies expanded access to previously hidden taxa, enabling high-throughput recovery of environmental microorganisms (Nichols et al., 2010). These advances were not incremental; they reopened ecological niches that had been chemically silent to researchers for decades.

Simultaneously, the search for new antibiotics has broadened beyond classical bacterial targets. For much of the twentieth century, discovery efforts focused on essential processes such as cell wall biosynthesis, protein translation, and DNA replication. While effective, these targets are now burdened by extensive resistance mechanisms. Contemporary research increasingly investigates alternative vulnerabilities, including specialized metabolic pathways and metallophore biosynthesis systems critical for nutrient acquisition (Ghssein et al., 2016; Mantravadi et al., 2019). By expanding the repertoire of druggable processes, researchers aim to bypass established resistance networks and identify mechanistic novelty.

Another conceptual shift involves targeting virulence rather than viability. Quorum sensing, biofilm formation, and cell-to-cell signaling pathways regulate pathogenic behavior without necessarily being essential for bacterial survival. Disrupting these systems may attenuate infection while exerting reduced selective pressure for resistance (Waters & Bassler, 2005; Kim et al., 2016). Though still evolving clinically, anti-virulence strategies illustrate a broader rethinking of antimicrobial therapy—less about eradication, perhaps, and more about disarmament.

The post-genomic era has dramatically accelerated discovery efforts. Genome sequencing reveals that microorganisms harbor numerous biosynthetic gene clusters encoding secondary metabolites, many of which remain silent under standard laboratory conditions. Bioinformatic tools such as antiSMASH enable rapid identification and annotation of these clusters, predicting chemical outputs and guiding experimental prioritization (Medema et al., 2011; Blin et al., 2017). Genome-guided approaches have reframed microbes as repositories of latent chemistry rather than merely culturable producers. Reviews of genome-driven natural product discovery emphasize how computational analysis now complements classical microbiology (Baltz, 2017; Rutledge & Challis, 2015).

These methods have already demonstrated tangible success. The discovery of teixobactin, for instance, underscored the value of combining innovative cultivation with genomic insight, revealing compounds with potent activity and limited detectable resistance (Ling et al., 2015). Renewed attention to bacterial natural products further reinforces their enduring relevance in the resistance era (Schneider, 2021; Wright, 2014). Rather than abandoning natural scaffolds, modern strategies seek to rediscover and reinterpret them through technological integration.

Ecological exploration has also gained renewed importance. Marine microbiomes represent chemically rich environments where nonribosomal peptide synthetases and polyketide synthases generate structurally diverse metabolites (Amoutzias et al., 2016). Actinobacteria isolated from subterranean caves and speleothems have yielded novel bioactive compounds, suggesting that extreme or isolated ecosystems foster unique biosynthetic capacities (Axenov-Gribanov et al., 2016). Antarctic environments, characterized by low temperatures and distinctive ecological pressures, have similarly revealed actinobacterial strains capable of antimicrobial metabolite production (Lee et al., 2012; Núñez-Montero & Barrientos, 2018). Even psychrotrophic bacterial communities in polar marine systems demonstrate inhibitory interactions indicative of antimicrobial chemistry (Lo Giudice et al., 2007). Collectively, these findings emphasize that ecological novelty often correlates with chemical innovation.

The challenges of antibacterial discovery remain substantial. Scientific, economic, and regulatory barriers intersect, slowing translation from laboratory discovery to clinical deployment (Payne et al., 2007; Brown & Wright, 2016). Yet the convergence of genome mining, advanced cultivation technologies, and expanded ecological sampling suggests that antibiotic innovation is not exhausted—it is evolving. Resistance may be inevitable as a biological phenomenon, but stagnation in discovery is not.

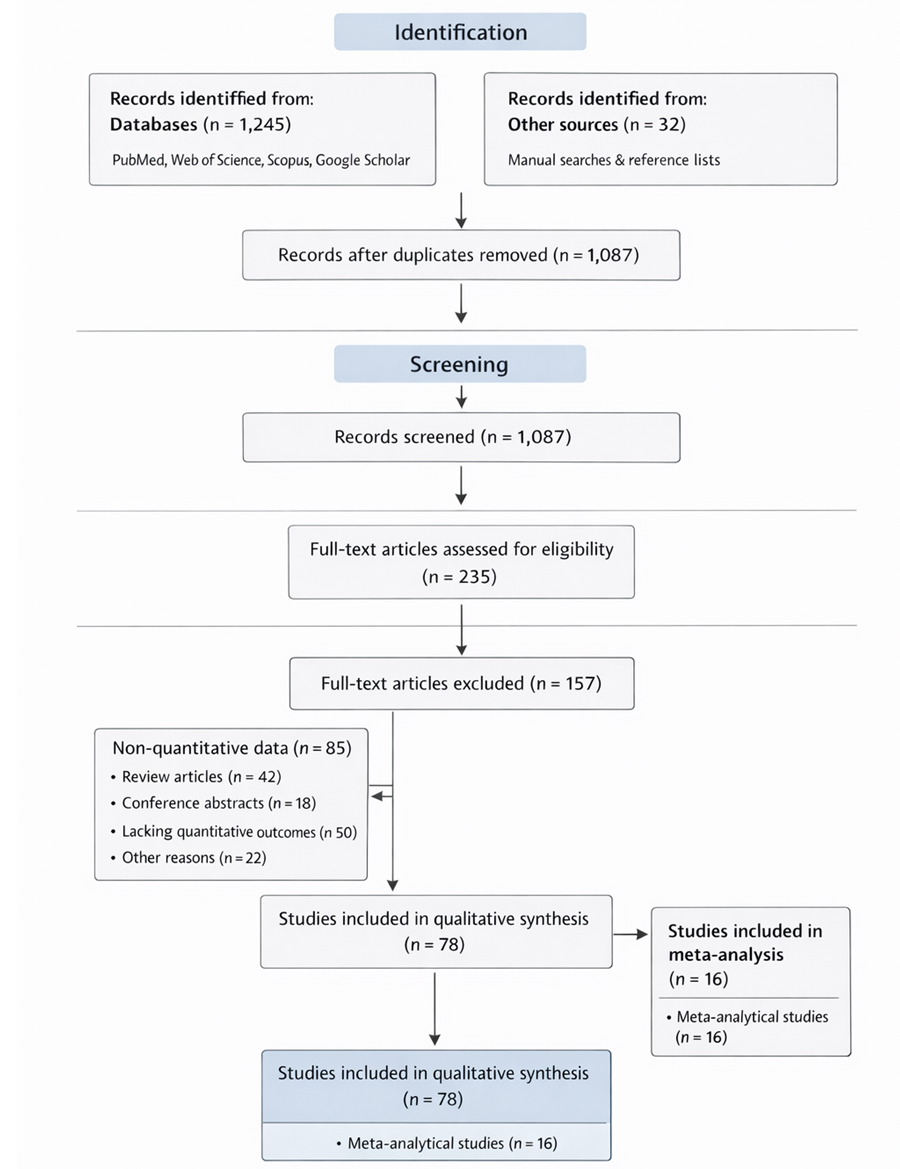

This systematic review and meta-analysis synthesize evidence across these emerging domains: novel molecular targets, genome-guided natural product discovery, anti-virulence strategies, and exploration of underexamined microbial habitats. By quantitatively and qualitatively assessing recent advances, it aims to clarify which approaches demonstrate consistent antimicrobial promise. In an era defined by resistance, reinvention is not optional. It is, increasingly, the only viable path forward.