Adeleke, B. S., & Babalola, O. O. (2021). Pharmacological potential of fungal endophytes associated with medicinal plants: A review. Journal of Fungi, 7(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7020147

Aly, A. H., Edrada-Ebel, R., Indriani, I. D., Wray, V., Müller, W. E. G., Totzke, F., Schächtele, C., Kubbutat, M. H. G., Lin, W. H., Proksch, P., et al. (2008). Cytotoxic metabolites from the fungal endophyte Alternaria sp. and their subsequent detection in its host plant Polygonum senegalense. Journal of Natural Products, 71(6), 972–980. https://doi.org/10.1021/np070447m

Amalfitano, C., Golubkina, N. A., Del Vacchio, L., Russo, G., Cannoniero, M., Somma, S., Morano, G., Cuciniello, A., & Caruso, G. (2019). Yield, antioxidant components, oil content, and composition of onion seeds are influenced by planting time and density. Plants, 8(8), 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8080293

Anand, U., Jacobo-Herrera, N., Altemimi, A., & Lakhssassi, N. (2019). A comprehensive review on medicinal plants as antimicrobial therapeutics: Potential avenues of biocompatible drug discovery. Metabolites, 9(11), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9110258

Andryukov, B., Mikhailov, V., & Besednova, N. (2019). The biotechnological potential of secondary metabolites from marine bacteria. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 7(7), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse7060176

Bhat, S. V., Nagasampagi, B. A., & Sivakumar, M. (2005). Chemistry of natural products. Springer.

Caruso, G., Golubkina, N., Tallarita, A., Abdelhamid, M. T., & Sekara, A. (2020). Biodiversity, ecology, and secondary metabolites production of endophytic fungi associated with Amaryllidaceae crops. Agriculture, 10(11), 533. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10110533

Cheng, Y.-B., Jensen, P. R., & Fenical, W. (2013). Cytotoxic and antimicrobial napyradiomycins from two marine-derived Streptomyces strains. European Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2013(18), 3751–3757. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.201300349

Conrado, R., Gomes, T. C., Roque, G. S. C., & De Souza, A. O. (2022). Overview of bioactive fungal secondary metabolites: Cytotoxic and antimicrobial compounds. Antibiotics, 11(12), 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11111604

De La Hoz-Romo, M. C., Díaz, L., & Villamil, L. (2022). Marine Actinobacteria: A new source of antibacterial metabolites to treat acne vulgaris disease—A systematic literature review. Antibiotics, 11(7), 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11070965

Domingues, J., Delgado, F., Gonçalves, J. C., Zuzarte, M., & Duarte, A. P. (2023). Mediterranean lavenders from section Stoechas: An undervalued source of secondary metabolites with pharmacological potential. Metabolites, 13(3), 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo13030337

Elshafie, H. S., Camele, I., & Mohamed, A. A. (2023). A comprehensive review on the biological, agricultural, and pharmaceutical properties of plant-origin secondary metabolites. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(4), 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24043266

Elshafie, H., Viggiani, L., Mostafa, M. S., El-Hashash, M. A., Camele, I., & Bufo, S. A. (2018). Biological activity and chemical identification of ornithine lipid produced by Burkholderia gladioli pv. agaricicola ICMP 11096 using LC-MS and NMR analyses. Journal of Biological Research – Bollettino della Società Italiana di Biologia Sperimentale, 91(1), 96–103. https://doi.org/10.4081/jbr.2017.6534

Gakuubi, M. M., Munusamy, M., Liang, Z.-X., & Ng, S. B. (2021). Fungal endophytes: A promising frontier for discovery of novel bioactive compounds. Journal of Fungi, 7(10), 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7100786

Hridoy, M., Gorapi, M. Z. H., Noor, S., Chowdhury, N. S., Rahman, M. M., Muscari, I., Masia, F., Adorisio, S., Delfino, D. V., & Mazid, M. A. (2022). Putative anticancer compounds from plant-derived endophytic fungi: A review. Molecules, 27, 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27010296

Iqbal, S., Begum, F., Rabaan, A. A., Aljeldah, M., Al Shammari, B. R., Alawfi, A., Alshengeti, A., Sulaiman, T., & Khan, A. (2023). Classification and multifaceted potential of secondary metabolites produced by Bacillus subtilis group: A comprehensive review. Molecules, 28(3), 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28030927

Jiao, W.-H., Yuan, W., Li, Z.-Y., Li, J., Li, L., Sun, J.-B., Gui, Y.-H., Wang, J., Ye, B.-P., & Lin, H.-W. (2018). Anti-MRSA actinomycins D1–D4 from the marine sponge-associated Streptomyces sp. LHW52447. Tetrahedron, 74(41), 5914–5919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2018.08.023

Keusgen, M., Schulz, H., Glodek, J., Krest, I., Krüger, H., Herchert, N., & Keller, J. (2002). Characterization of some Allium hybrids by aroma precursors, aroma profiles, and alliinase activity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 50(10), 2884–2890. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf011331d

Kim, C. K., Eo, J. K., & Eom, A. H. (2013). Diversity and seasonal variation of endophytic fungi isolated from three conifers in Mt. Taehwa, Korea. Mycobiology, 41, 82–85. https://doi.org/10.5941/MYCO.2013.41.2.82

Kobayashi, J., & Tsuda, M. (2004). Amphidinolides, bioactive macrolides from symbiotic marine dinoflagellates. Natural Product Reports, 21(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1039/b310427n

Kunz, A. L., Labes, A., Wiese, J., Bruhn, T., Bringmann, G., & Imhoff, J. F. (2014). Nature's lab for derivatization: New and revised structures of a variety of streptophenazines produced by a sponge-derived Streptomyces strain. Marine Drugs, 12(3), 1699–1714. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12041699

Lin, T., Wang, G., Zhou, Y., Zeng, D., Liu, X., Ding, R., Jiang, X., Zhu, D., Shan, W., & Chen, H. (2014). Structure elucidation and biological activity of two new trichothecenes from an endophyte, Myrothecium roridum. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 62(25), 5993–6000. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf501724a

McPhail, K. L., Correa, J., Linington, R. G., González, J., Ortega-Barría, E., Capson, T. L., & Gerwick, W. H. (2007). Antimalarial linear lipopeptides from a Panamanian strain of the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. Journal of Natural Products, 70(6), 984–988. https://doi.org/10.1021/np0700772

Meena, H., Hnamte, S., & Siddhardha, B. (2019). Secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi: Chemical diversity and application. In B. Singh (Ed.), Advances in Endophytic Fungal Research (Vol. 1, pp. 145–169). Springer, Cham, Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03589-1_7

Nawrot-Chorabik, K., Sulkowska, M., & Gumulak, N. (2022). Secondary metabolites produced by trees and fungi: Achievements so far and challenges remaining. Forests, 13(8), 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13081338

Newman, D. J., & Cragg, G. M. (2020). Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. Journal of Natural Products, 83(3), 770–803. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01285

Nisa, H., Kamili, A. N., Nawchoo, I. A., Shafi, S., Shameem, N., & Bandh, S. A. (2015). Fungal endophytes as prolific source of phytochemicals and other bioactive natural products: A review. Microbial Pathogenesis, 82, 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2015.04.001

Nurjannah, L., Azhari, A., & Supratman, U. (2023). Secondary metabolites of endophytes associated with the Zingiberaceae family and their pharmacological activities. Scientia Pharmaceutica, 91(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm91010003

Ogawa, H., Iwasaki, A., Sumimoto, S., Kanamori, Y., Ohno, O., Iwatsuki, M., Ishiyama, A., Hokari, R., Otoguro, K., Omura, S., et al. (2016). Janadolide, a cyclic polyketide-peptide hybrid possessing a tert-butyl group from an Okeania sp. marine cyanobacterium. Journal of Natural Products, 79(7), 1862–1866. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00171

Orefice, I., Balzano, S., Romano, G., & Sardo, A. (2023). Amphidinium spp. as a source of antimicrobial, antifungal, and anticancer compounds. Life, 13(11), 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13112164

Palomo, S., González, I., de la Cruz, M., Martín, J., Tormo, J. R., Anderson, M., Hill, R. T., Vicente, F., Reyes, F., & Genilloud, O. (2013). Sponge-derived Kocuria and Micrococcus spp. as sources of the new thiazolyl peptide antibiotic kocurin. Marine Drugs, 11(4), 1071–1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11041071

Pham, J. V., Yilma, M. A., Feliz, A., Majid, M. T., Maffetone, N., Walker, J. R., et al. (2019). A review of the microbial production of bioactive natural products and biologics. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 1404. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01404

Rönsberg, D., Debbab, A., Mándi, A., Vasylyeva, V., Böhler, P., Stork, B., Engelke, L., Hamacher, A., Sawadogo, R., Diederich, M., et al. (2013). Pro-apoptotic and immunostimulatory tetrahydroxanthone dimers from the endophytic fungus Phomopsis longicolla. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 78(24), 12409–12425. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo402066b

Sanchez, L. M., Lopez, D., Vesely, B. A., Della Togna, G., Gerwick, W. H., Kyle, D. E., & Linington, R. G. (2010). Almiramides A–C: Discovery and development of a new class of leishmaniasis lead compounds. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 53(10), 4187–4197. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm100265s

Sánchez-Suárez, J., Coy-Barrera, E., Villamil, L., & Díaz, L. (2020). Streptomyces-derived metabolites with potential photoprotective properties—A systematic literature review and meta-analysis on the reported chemodiversity. Molecules, 25(14), 3221. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25143221

Soares, D. A., Rosa, L. H., Silva, J. M. F., & Pimenta, R. S. (2017). A review of bioactive compounds produced by endophytic fungi associated with medicinal plants. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi: Ciências Naturais, 12, 331–352. https://doi.org/10.46357/bcnaturais.v12i3.83

Song, G., Zhang, Z., Niu, X., & Zhu, D. (2023). Secondary metabolites from fungi Microsphaeropsis spp.: Chemistry and bioactivities. Journal of Fungi, 9(11), 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9111093

Srinivasan, R., Kannappan, A., Shi, C., & Lin, X. (2021). Marine bacterial secondary metabolites: A treasure house for structurally unique and effective antimicrobial compounds. Marine Drugs, 19(10), 530. https://doi.org/10.3390/md19100530

Sudharshana, T. N., Venkatesh, H. N., Nayana, B., Manjunath, K., & Mohana, D. C. (2019). Antimicrobial and antimycotoxigenic activities of endophytic Alternaria alternata isolated from Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don: Molecular characterisation and bioactive compound isolation. Mycology, 10(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501203.2018.1541933

Sulaiman, M., Nissapatorn, V., Rahmatullah, M., Paul, A. K., Rajagopal, M., Rusdi, N. A., et al. (2022). Antimicrobial secondary metabolites from the mangrove plants of Asia and the Pacific. Marine Drugs, 20(10), 643. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20100643

Swamy, M. K., Tuyelee, D., Nandy, S., Mukherjee, A., Pandey, D. K., & Dey, A. (2022). Endophytes for the production of anticancer drug, paclitaxel. In M. K. Swamy, T. Pullaiah, & Z.-S. Chen (Eds.), Paclitaxel: Sources, Chemistry, Anticancer Actions, and Current Biotechnology (pp. 203–228). Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90951-8.00012-6

Tripathi, A., Puddick, J., Prinsep, M. R., Kanekiyo, M., Young, K. A., Pilon, M., Simon, N. W., & Tan, L. T. (2010). Lagunamides A and B, cytotoxic and antimalarial cyclodepsipeptides from the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. Journal of Natural Products, 73(11), 1810–1814. https://doi.org/10.1021/np100442x

Vallavan, V., Krishnasamy, G., Zin, N. M., & Latif, M. A. (2020). A review on antistaphylococcal secondary metabolites from Basidiomycetes. Molecules, 25(24), 5848. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25245848

Wang, Y., Liu, H. X., Chen, Y. C., Sun, Z. H., Li, H. H., Li, S. N., Yan, M. L., & Zhang, W. M. (2017). Two new metabolites from the endophytic fungus Alternaria sp. A744 derived from Morinda officinalis. Molecules, 22(5), 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22050765

Xu, K., Wei, X. L., Xue, L., Zhang, Z. F., & Zhang, P. (2020). Antimicrobial meroterpenoids and erythritol derivatives isolated from the marine-algal-derived endophytic fungus Penicillium chrysogenum XNM-12. Marine Drugs, 18, 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/md18110578

Xu, S., Li, M., Hu, Z., Shao, Y., Ying, J., & Zhang, H. (2023). The potential use of fungal co-culture strategy for discovery of new secondary metabolites. Microorganisms, 11(2), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11020464

Yao, Q., Wang, J., Zhang, X., Nong, X., Xu, X., & Qi, S. (2014). Cytotoxic polyketides from the deep-sea-derived fungus Engyodontium album DFFSCS021. Marine Drugs, 12(12), 5902–5915. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12125902

Yi, W., Li, Q., Song, T., Chen, L., Li, X.-C., Zhang, Z., & Lian, X.-Y. (2019). Isolation, structure elucidation, and antibacterial evaluation of the metabolites produced by the marine-sourced Streptomyces sp. ZZ820. Tetrahedron, 75(9), 1186–1193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2019.01.025

Youssef, D. T. A., Mufti, S. J., Badiab, A. A., & Shaala, L. A. (2022). Anti-infective secondary metabolites of the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya morphotype between 1979 and 2022. Marine Drugs, 20(12), 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20120768

Zhang, H., Ruan, C., Bai, X., Zhang, M., Zhu, S., & Jiang, Y. (2016). Isolation and identification of the antimicrobial agent beauvericin from the endophytic F5-19 with NMR and ESI-MS/MS. BioMed Research International, 2016, Article 1084670. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1084670

Zheng, R., Li, S., Zhang, X., & Zhao, C. (2021). Biological activities of some new secondary metabolites isolated from endophytic fungi: A review study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(2), 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22020959

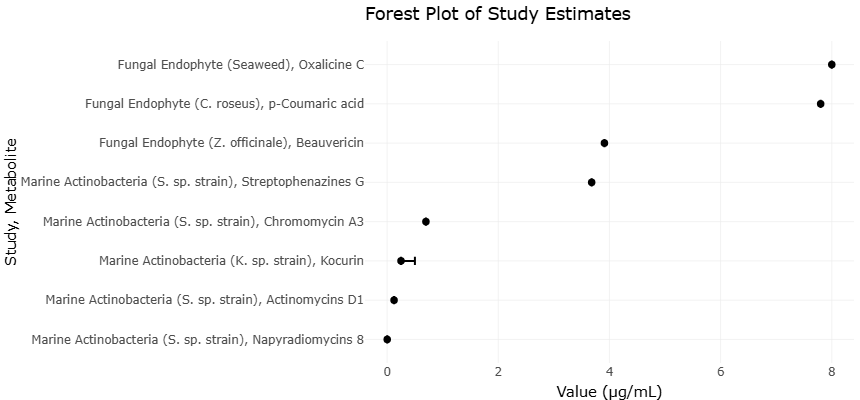

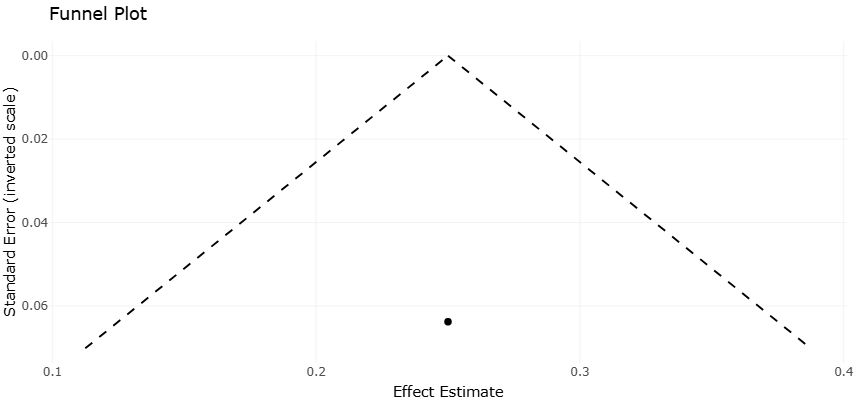

Figure 3. Comparative antimicrobial efficacy of secondary metabolites expressed as MIC values (µg/mL). Visual representation of study precision versus effect size to evaluate potential small-study effects and publication bias in the meta-analysis.

Figure 3. Comparative antimicrobial efficacy of secondary metabolites expressed as MIC values (µg/mL). Visual representation of study precision versus effect size to evaluate potential small-study effects and publication bias in the meta-analysis.