1. Introduction

In recent years, scientific interest in the relationship between gut health and mental well-being has surged, largely driven by the groundbreaking discovery of the gut–brain axis—a complex, bidirectional communication network linking the gastrointestinal (GI) tract with the central nervous system (CNS) (Cryan & O’Mahony, 2011). This intricate system allows for constant biochemical and neural exchanges, ensuring that changes in the gut environment can directly influence emotional and cognitive processes. Traditionally, the brain was considered the central command center, functioning independently from other organ systems. However, this paradigm has shifted dramatically as emerging evidence reveals that the gut microbiota—the vast community of bacteria, fungi, and viruses residing in the intestines—plays a crucial role in regulating mood, cognition, stress responses, and overall mental health (Dinan & Cryan, 2017; Furness, 2012).

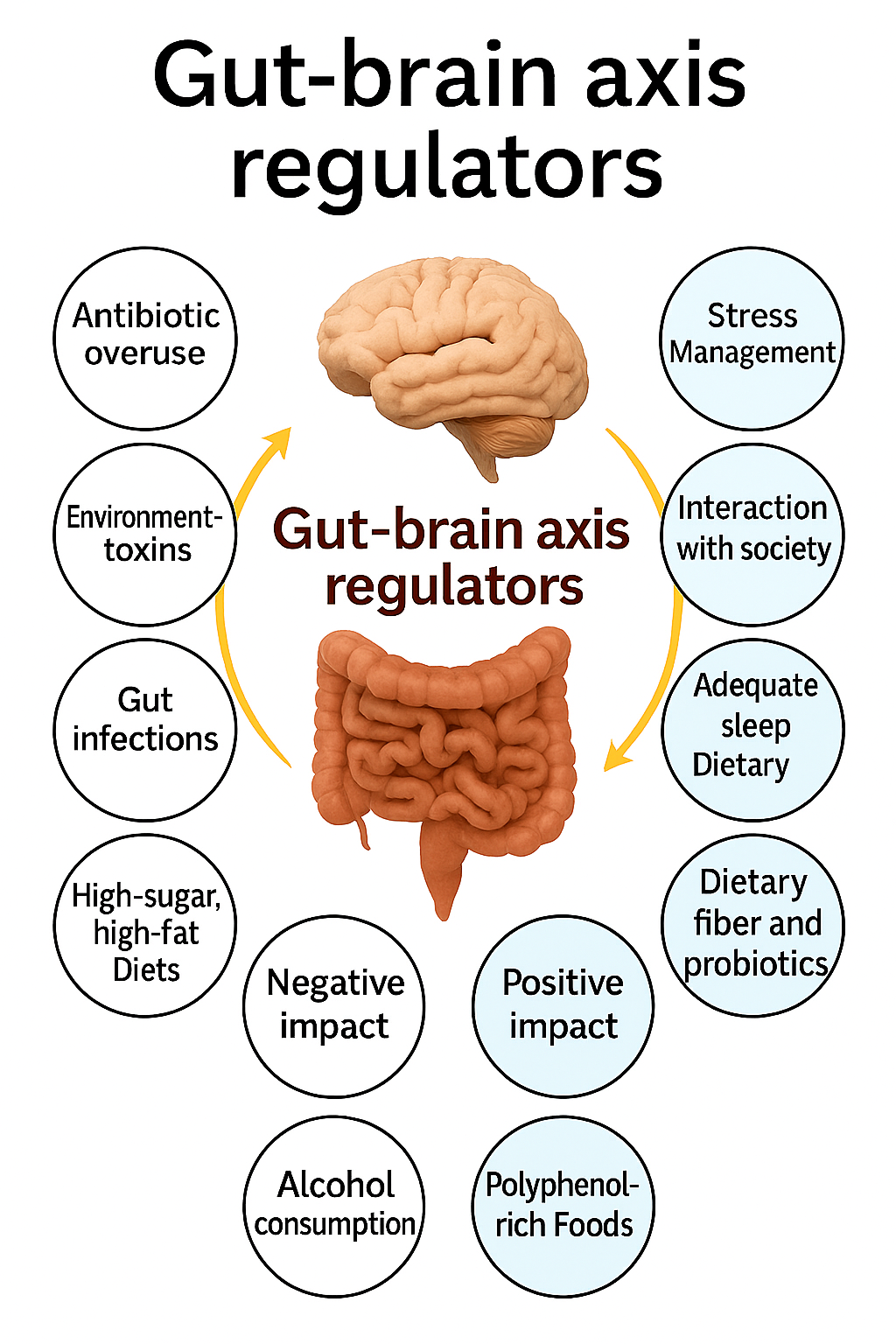

The adage “you are what you eat” has gained new scientific meaning in the context of microbial ecology and mental health. Dietary habits are now known to shape the gut microbiome’s composition, diversity, and stability, influencing host metabolism and neurochemical balance (Mayer, Tillisch, & Gupta, 2015; Ouwehand, Lagström, Wacklin, & Salminen, 2016). A balanced diet rich in fiber, polyphenols, and fermented foods can promote the growth of beneficial microorganisms such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which are associated with improved gut integrity and neurochemical regulation. In contrast, diets high in refined sugars, fats, and processed foods disrupt microbial diversity, promoting dysbiosis—a condition linked to inflammation, impaired neurotransmitter production, and heightened vulnerability to mood disorders (Cani et al., 2008; Bischoff et al., 2014).

Probiotics—live microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts—have emerged as a natural means of restoring microbial balance (Benton, Williams, & Brown, 2007). Found in fermented foods such as yogurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, and kefir, probiotics can modulate intestinal permeability, reduce inflammation, and influence the gut–brain axis through multiple biological mechanisms (Arseneault-Bréard et al., 2012). The most studied probiotic genera, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, have demonstrated psychotropic-like effects in both animal models and human clinical trials, leading to the coining of the term psychobiotics—probiotics that confer mental health benefits by interacting with the gut–brain axis (Dinan, Stanton, & Cryan, 2013).

Experimental evidence supports the ability of probiotics to modulate neurotransmitter systems involved in mood regulation. For example, Lactobacillus rhamnosus ingestion has been shown to alter central GABA receptor expression, leading to reduced anxiety- and depression-like behavior in mice (Bravo et al., 2011). Similarly, certain Bifidobacterium strains enhance serotonin biosynthesis in the gut by influencing the host’s tryptophan metabolism (Yano et al., 2015). Given that approximately 90% of the body’s serotonin—a key neurotransmitter in mood regulation—is synthesized in the gut, microbial modulation of serotonin pathways provides a direct biochemical link between intestinal health and emotional state (Kelly et al., 2015).

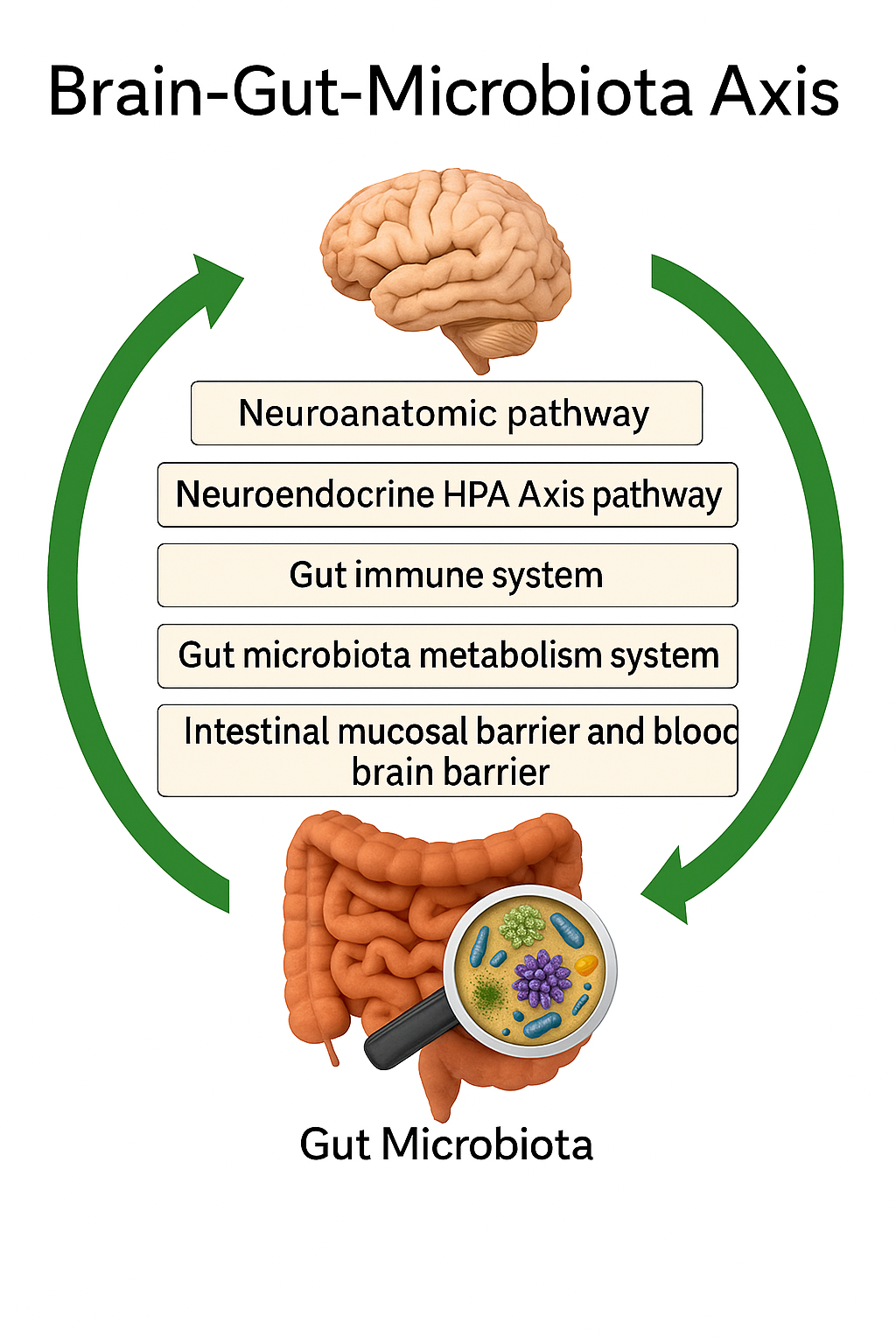

The gut–brain axis operates through multiple interrelated mechanisms, including neural, immune, and endocrine signaling pathways. The vagus nerve, a critical conduit connecting the gut to the brainstem, allows for rapid bidirectional communication and plays a pivotal role in regulating mood, stress, and anxiety (Forsythe, Kunze, & Bienenstock, 2012; Ait-Belgnaoui et al., 2012). Additionally, gut microbes produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate—through the fermentation of dietary fibers. These SCFAs modulate neuroinflammation, strengthen the intestinal barrier, and influence the production of neuroactive molecules (Dalile et al., 2017). When the gut barrier becomes compromised, increased intestinal permeability, often referred to as “leaky gut,” allows pro-inflammatory molecules to enter systemic circulation, triggering neuroinflammatory responses associated with depression and anxiety (Bischoff et al., 2014; Agudelo et al., 2014).

Several clinical and preclinical studies further substantiate the therapeutic potential of probiotics in alleviating mood disorders. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175 significantly reduced depression and anxiety scores in human participants, likely by enhancing intestinal barrier integrity and reducing systemic inflammation (Messaoudi et al., 2011). Similarly, Akkasheh et al. (2016) found that probiotic supplementation improved depressive symptoms and metabolic profiles in patients with major depressive disorder. In animal models, probiotic administration has been shown to reverse stress-induced behavioral changes and normalize hippocampal serotonin levels, emphasizing the microbiota’s role in neuroplasticity and emotional regulation (Desbonnet et al., 2010; Clarke et al., 2013).

While these findings are promising, significant challenges remain in translating preclinical results into consistent clinical outcomes. Human studies often vary in probiotic strains, dosage, and duration, making it difficult to identify standardized therapeutic protocols (Bercik, Collins, & Verdu, 2012; Collins & Bercik, 2013). Moreover, individual differences in microbiome composition, diet, genetics, and lifestyle can influence probiotic efficacy. Another limitation lies in the transient nature of probiotic colonization—many strains do not permanently integrate into the host microbiome, necessitating continuous intake for sustained benefits (Ouwehand et al., 2016). Therefore, a deeper understanding of host–microbe interactions, microbial metabolism, and personalized nutrition is required to optimize the clinical use of psychobiotics.

Nonetheless, the emerging evidence underscores the profound interdependence between the gut and brain. Recognizing the gut as a “second brain” shifts the perspective of mental health from a purely neurological framework to a holistic, systemic one that includes diet, microbial ecology, and immune function. This integrated approach opens new avenues for the prevention and treatment of mental disorders, emphasizing that mental wellness begins in the gut. As research continues to unravel the complexities of the microbiome–gut–brain axis, probiotics and dietary interventions hold great promise as complementary strategies for managing stress, anxiety, and depression (Cryan & Dinan, 2012; Dinan, Cryan, & Stanton, 2013).

In conclusion, the gut–brain axis represents a revolutionary paradigm in neuroscience and psychiatry, revealing how the trillions of microbes in our intestines can influence mood, cognition, and behavior. Probiotics, as modulators of this axis, provide a promising, natural approach to enhancing emotional resilience and cognitive performance. By understanding how dietary choices and microbial diversity affect mental well-being, both individuals and healthcare professionals can adopt holistic strategies to foster long-term psychological health.