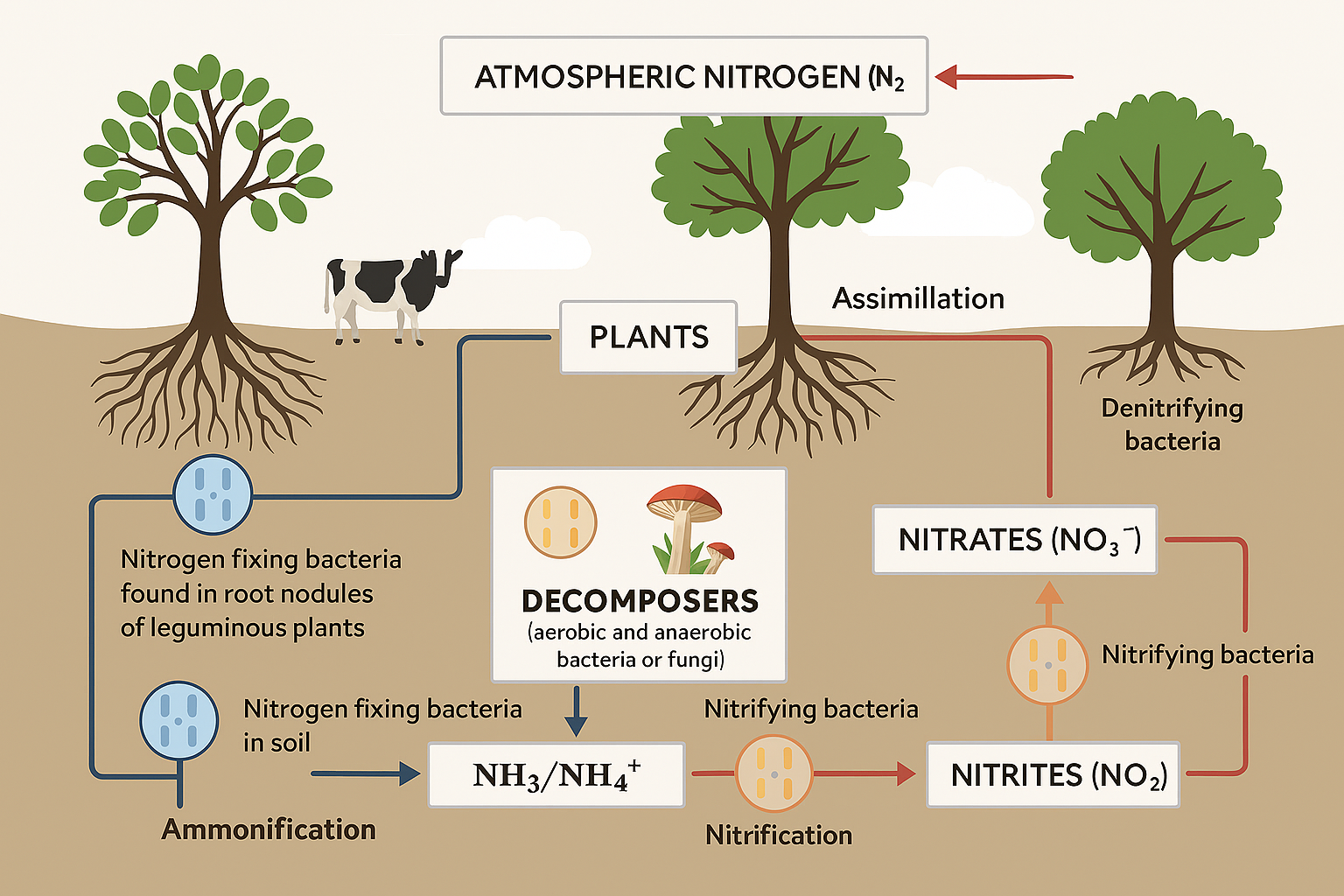

Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) is mediated by a wide array of diazotrophic microorganisms, which can be categorized into symbiotic, associative, and free-living nitrogen fixers. Each group contributes substantially to plant nitrogen nutrition, soil fertility, and sustainable agriculture. These microbes convert atmospheric nitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3), a form readily absorbed by plants. Their involvement in the global nitrogen cycle is critical for maintaining agricultural productivity while reducing dependence on synthetic nitrogen fertilizers (Ladha & Reddy, 2003; Kennedy & Islam, 2001). A comprehensive understanding of the diversity, interactions, and ecological roles of these microorganisms is essential for optimizing their use in sustainable farming systems (Table 1).

Table 1. Types of Nitrogen-Fixing Microorganisms and Their Characteristics

|

Microbial Group

|

Representative Genera

|

Host/Association

|

Mechanism of Nitrogen Fixation

|

Key Features

|

References

|

|

Symbiotic

|

Rhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Frankia

|

Legumes (soybean, pea, clover), actinorhizal plants

|

Formation of root nodules; nitrogenase-mediated conversion of N2 to NH3

|

High nitrogen fixation efficiency; host-specific; nodulation regulated by flavonoids and nod genes

|

Adesemoye et al., 2009; Benson & Silvester, 1993; Oldroyd & Downie, 2008; Liu & Murray, 2016

|

|

Associative

|

Azospirillum, Herbaspirillum

|

Cereal crops (wheat, maize, rice)

|

Colonizes rhizosphere and root surfaces; fixes nitrogen in proximity to roots

|

Improves root growth; promotes plant growth via phytohormones; moderate nitrogen contribution

|

Bashan, 1998; Kloepper et al., 2004; Hirel et al., 2011

|

|

Free-living

|

Azotobacter, Clostridium, Cyanobacteria

|

Soil and non-leguminous plants

|

Fixes nitrogen independently in soil

|

Tolerant to environmental stress; moderate nitrogen fixation; can enhance soil organic matter

|

Kennedy & Islam, 2001; Mus et al., 2016; Santi et al., 2013

|

Note: This table categorizes nitrogen-fixing microorganisms into symbiotic, associative, and free-living groups, highlighting their host specificity, mechanism of nitrogen fixation, and key functional traits.

3.1 Symbiotic Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria

Symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria form mutualistic associations with specific host plants, particularly legumes, to facilitate nitrogen fixation. The most extensively studied symbionts belong to the genera Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium, which colonize roots of legumes such as soybean (Glycine max), pea (Pisum sativum), clover (Trifolium spp.), and alfalfa (Medicago sativa) (Van Heerwaarden et al., 2018; Beyan et al., 2018). These bacteria induce root nodule formation, specialized structures where nitrogen fixation occurs.

Nodule initiation involves a sophisticated chemical signaling exchange between the plant and bacterium. Legume roots release flavonoids, which attract compatible Rhizobium strains (Liu & Murray, 2016). In response, Rhizobium produces Nod factors, lipochitooligosaccharides that trigger root hair curling, cortical cell division, and infection thread formation (Perret, Staehelin, & Broughton, 2000). Once inside the nodule, bacteria differentiate into bacteroids, capable of reducing atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia via the nitrogenase enzyme complex. The host plant supplies carbohydrates and essential nutrients, while the bacteria provide fixed nitrogen in return (Dixon & Kahn, 2004; Oldroyd & Downie, 2008). Other symbiotic genera, such as Sinorhizobium, Mesorhizobium, and Bradyrhizobium, display specificity toward particular legume species, emphasizing the importance of host compatibility (Gage, 2004).

3.2 Non-Leguminous Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixers

Although legume-associated BNF is widely recognized, some non-leguminous plants form symbiotic nitrogen-fixing partnerships with actinobacteria such as Frankia. Actinorhizal plants, including alder (Alnus spp.), casuarina (Casuarina spp.), and bayberry (Myrica spp.), harbor Frankia in root nodules, enabling atmospheric nitrogen fixation (Benson & Silvester, 1993; Santi, Bogusz, & Franche, 2013). Actinorhizal symbioses are particularly important in forest ecosystems and nutrient-poor soils, contributing to soil nitrogen enrichment without requiring seed inoculation (Dawson, 2008). These interactions illustrate the ecological relevance of non-legume nitrogen-fixing partnerships.

3.3 Associative Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria

Associative nitrogen fixers colonize plant roots or internal tissues without forming nodules. These microbes reside in the rhizosphere or endophytically within plant tissues and enhance nitrogen availability indirectly through root exudates and microbial interactions (Adesemoye, Torbert, & Kloepper, 2009).

Azospirillum: A Key Associative Fixer

Azospirillum is a well-studied facultative endophyte that colonizes roots of cereals and grasses, including wheat (Triticum aestivum), maize (Zea mays), and rice (Oryza sativa) (Bashan, 1998; Bashan & de-Bashan, 2010). This bacterium promotes plant growth not only through nitrogen fixation but also by synthesizing phytohormones such as indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), gibberellins, and cytokinins, which stimulate root elongation and enhance nutrient and water uptake efficiency (Steenhoudt & Vanderleyden, 2000).

Herbaspirillum and Gluconacetobacter

Other associative nitrogen fixers, including Herbaspirillum and Gluconacetobacter, inhabit crops such as sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), rice, and wheat (Boddey et al., 2003; Ravikumar et al., 2007). Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus is particularly effective in fixing nitrogen within sugarcane stems, reducing the need for chemical fertilizers and improving sustainability in sugarcane cultivation (Reis et al., 2000).

3.4 Free-Living Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria

Free-living nitrogen fixers function independently of plant hosts and play critical roles in soil nitrogen enrichment. These organisms contribute to nitrogen availability in both agricultural and natural ecosystems.

Azotobacter: A Model Free-Living Fixer

Azotobacter is a widely studied aerobic diazotroph capable of efficient nitrogen fixation (Kennedy & Islam, 2001). It also secretes polysaccharides that improve soil structure and water retention, alongside growth-promoting compounds such as IAA, gibberellins, and vitamins (Bashan, 1998).

Clostridium and Beijerinckia

Anaerobic bacteria like Clostridium fix nitrogen under oxygen-limited conditions, such as waterlogged soils, while Beijerinckia species thrive in acidic soils, supporting nitrogen availability where other diazotrophs are less efficient (Kennedy & Islam, 2001; Bashan, 1998).

3.5 Role in Soil Fertility

Free-living nitrogen fixers enhance soil nitrogen pools by releasing ammonia and related compounds that plants can absorb. Their role is especially significant in organic and low-input farming systems (Bashan, 1998). Although less efficient than symbiotic or associative bacteria due to the lack of continuous plant-derived energy, their contributions to soil fertility are indispensable. Environmental factors such as pH, moisture, and carbon availability strongly influence free-living nitrogen fixation activity (Hungria & Vargas, 2000; Ladha & Reddy, 2003).