3.1 Glyphosate: Mechanism of Action and Safety Assumptions

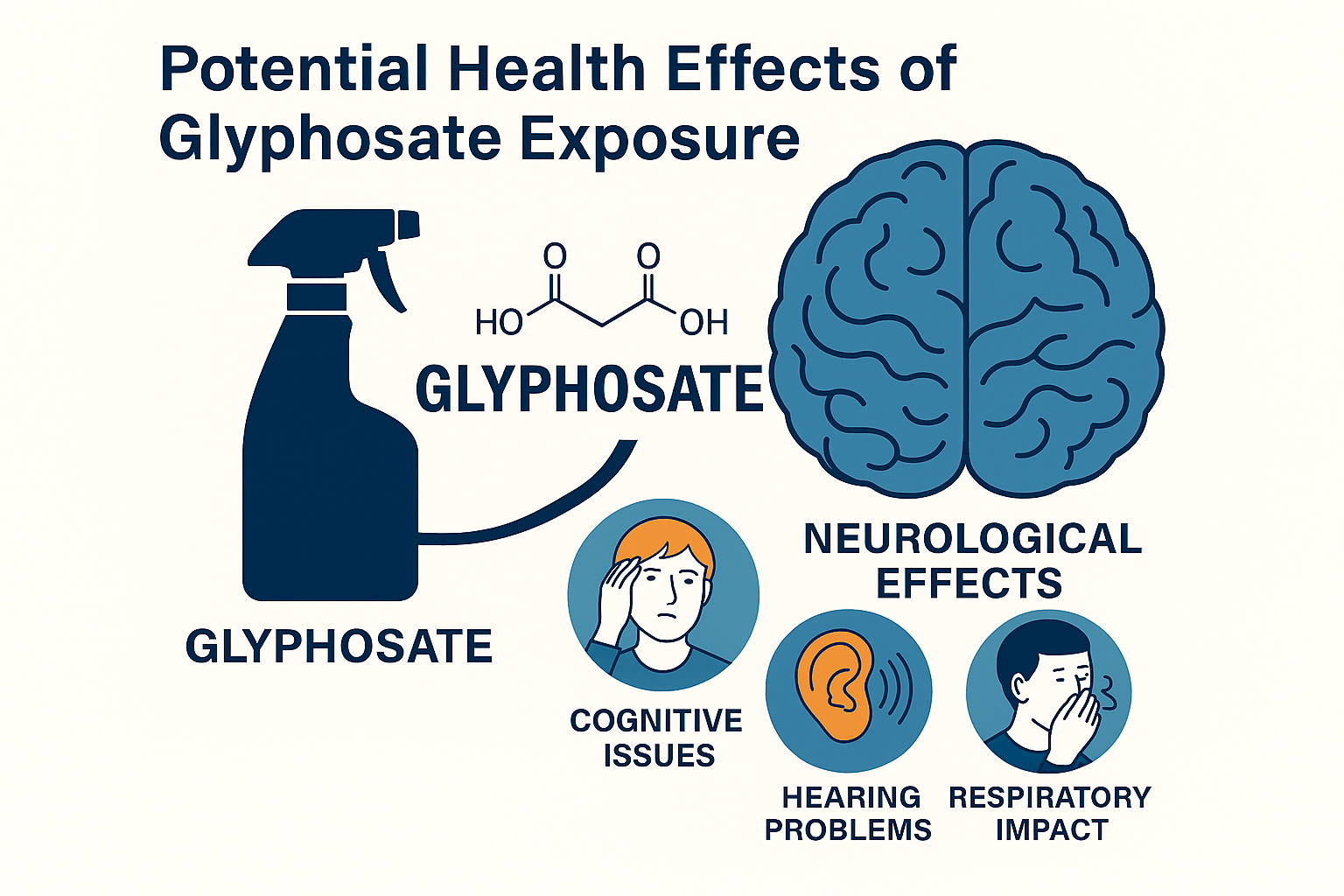

Glyphosate functions primarily as a non-selective herbicide by inhibiting the enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) within the shikimate pathway, a critical metabolic route for synthesizing aromatic amino acids in plants and many microorganisms (Funke et al., 2006; Duke & Powles, 2008). Because animals and humans lack this pathway, glyphosate was initially considered non-toxic to higher organisms, a perception that contributed to its global dominance in agriculture, particularly with glyphosate-resistant genetically modified crops (Benbrook, 2016; Jezierska-Tys et al., 2021). As summarized in Table 1, glyphosate exposure consistently disrupts beneficial microbial populations across soil, gut, and aquatic systems while favoring the proliferation of pathogenic or resistant organisms. This imbalance undermines critical ecosystem services, including nutrient cycling, immune modulation, and primary productivity, suggesting that microbial vulnerability represents a major, previously underestimated pathway of harm. The ecological disruptions outlined in Table 1 provide a foundational explanation for the broader health and environmental outcomes increasingly associated with glyphosate use.

Table 1: Effects of Glyphosate on Microbial Communities

|

System

|

Beneficial Microbes Affected

|

Pathogens/Resistant Microbes Promoted

|

Observed Consequences

|

|

Soil Microbiome

|

Rhizobium spp., Mycorrhizal fungi

|

Fusarium spp.

|

Reduced nitrogen fixation, impaired nutrient cycling, increased plant diseases

|

|

Human Gut Microbiome

|

Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium

|

Clostridium spp., other resistant bacteria

|

Dysbiosis, immune dysfunction, metabolic disorders

|

|

Aquatic Microbiome

|

Phytoplankton, oxygen-producing microbes

|

Cyanobacteria

|

Harmful algal blooms, eutrophication, biodiversity loss, oxygen depletion

|

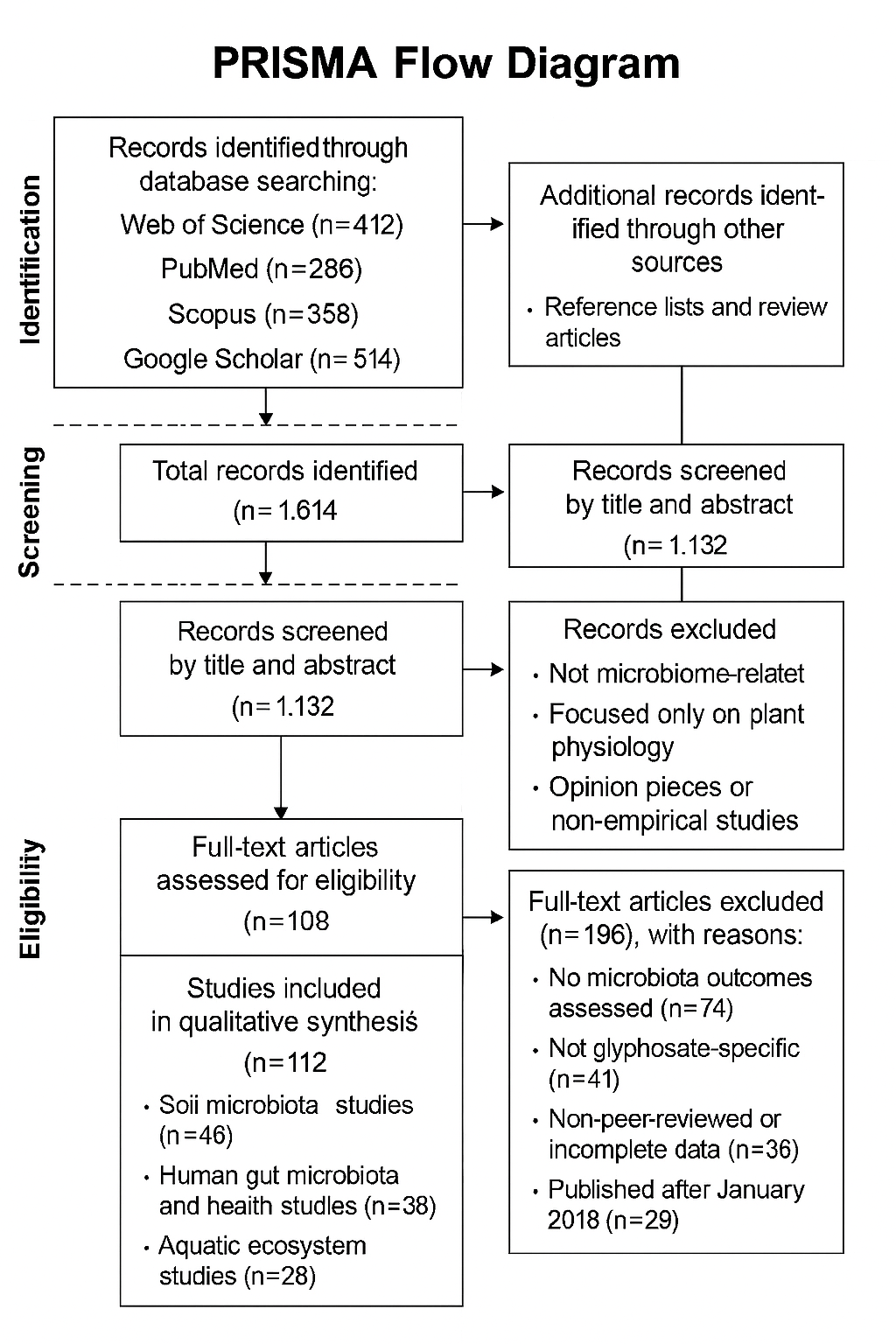

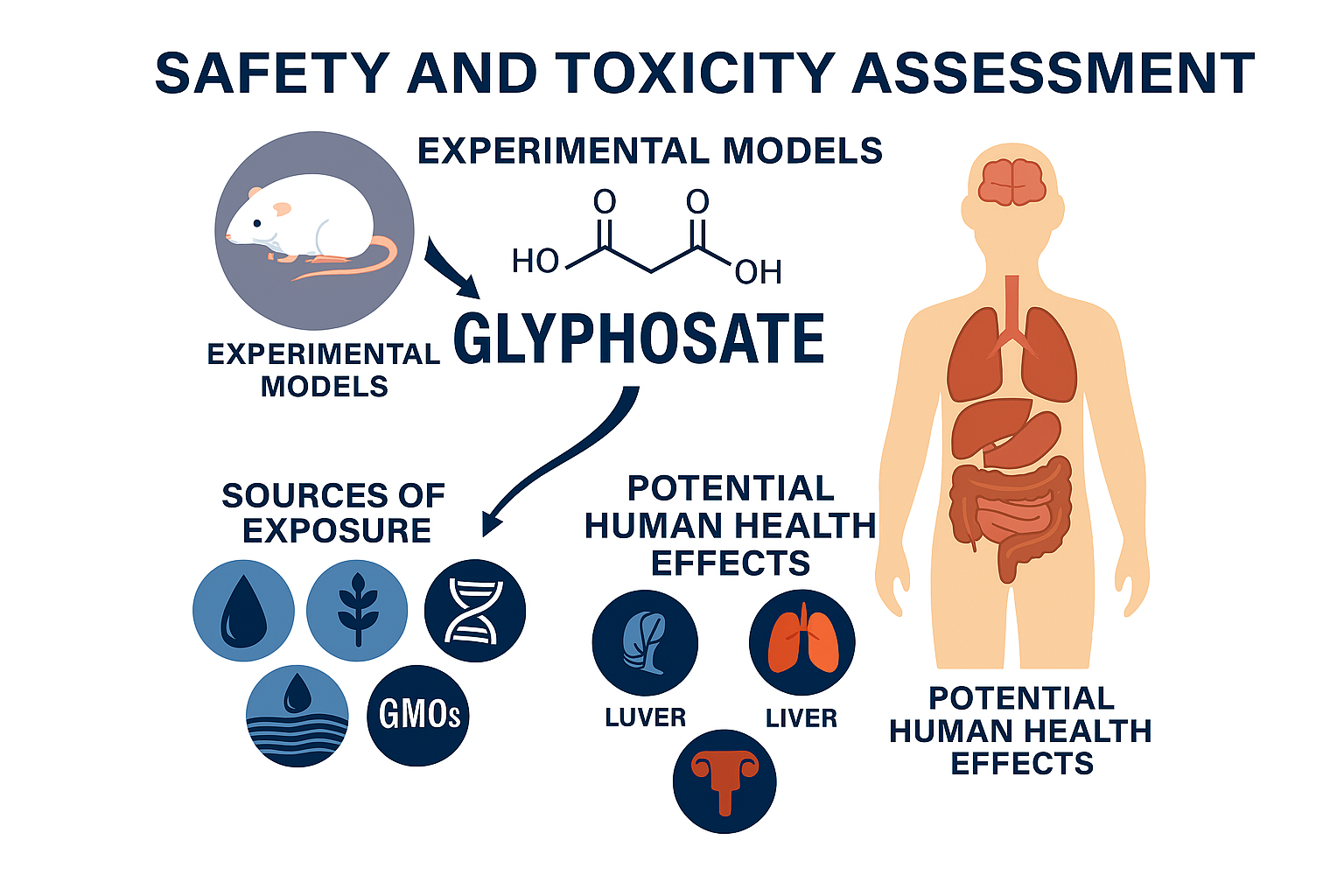

However, emerging evidence challenges this assumption of safety. Many microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, rely on the shikimate pathway, making them vulnerable to glyphosate inhibition (Claus et al., 2011; Flint et al., 2012). These microbes are central to ecological processes in soil, water, and the human gut, suggesting that glyphosate’s widespread use may have cascading effects on ecosystem function and public health (Krüger et al., 2013; Shehata et al., 2013) (Figure 2). These systemic effects are conceptually reinforced by Figure 2, which illustrates how chemical exposure may translate into multi-organ health risks, particularly during sensitive developmental periods. While Figure 2 does not imply direct causality, it contextualizes microbial dysregulation within a wider biological framework, linking environmental exposure to neurological, metabolic, and respiratory outcomes. Together, Table 1 and Figure 2 underscore the need to reconsider glyphosate safety beyond plant-specific toxicity models, emphasizing microbial integrity as a central determinant of both ecosystem resilience and human health.

Figure 1: Potential Health Effects of Glyphosate Exposure. Mother’s Glyphosate Exposure During Pregnancy Increases Child’s Risk of Poor Brain Function and Development. This figure illustrates the possible health impacts associated with glyphosate exposure, including neurological effects, cognitive issues, hearing problems, and respiratory impact. The schematic emphasizes the link between chemical exposure and multi-system health risks. (Courtesy of image from Mesnage et al., 2015)

3.2 Impacts on Soil Microbiota

Soil is a dynamic ecosystem where microbial communities sustain fertility, regulate nutrient cycling, and support plant health (Zobiole, et al., 2011; Ratcliff et al., 2006). Glyphosate exposure disrupts these communities by suppressing beneficial organisms and facilitating the growth of pathogens. For instance, glyphosate reduces populations of nitrogen-fixing bacteria, such as Rhizobium, impairing plant nutrient uptake, and negatively affects mycorrhizal fungi, reducing soil productivity (Kremer & Means, 2009; Johal & Huber, 2009; Jezierska-Tys et al., 2021).

Pathogenic fungi, including Fusarium species, often proliferate under glyphosate exposure, increasing soilborne disease risk and threatening long-term crop sustainability (Neves et al., 2019). Glyphosate’s persistence in soil, amplified by repeated applications, intensifies these disruptions, ultimately undermining soil resilience and ecosystem services crucial for sustainable agriculture (Van Bruggen et al., 2018).

3.3 Effects on the Human Gut Microbiome

The human gut microbiome is essential for metabolism, immune regulation, and overall health (Cryan & Dinan, 2012). Glyphosate exposure has been shown to selectively inhibit beneficial bacteria, including Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, while allowing resistant pathogens such as Clostridium to persist (Shehata et al., 2013; Motto et al., 2018; Balbuena et al., 2015). This microbial imbalance, or dysbiosis, is associated with metabolic disorders, inflammatory diseases, and immune dysfunction (Mesnage et al., 2015; Cryan & Dinan, 2012).

Glyphosate residues have also been detected in food products and human urine, raising concerns about chronic low-dose exposure (Mao et al., 2018). Although regulatory agencies consider these levels below harmful thresholds, the cumulative impact on gut microbial diversity remains uncertain, particularly given that most studies prior to 2018 focused on acute toxicity rather than microbiome-specific outcomes.

3.4 Glyphosate in Aquatic Ecosystems

Aquatic ecosystems are highly susceptible to glyphosate contamination via agricultural runoff. Studies have documented reductions in phytoplankton populations, disruptions of microbial food webs, and the promotion of eutrophication in freshwater habitats (Vera et al., 2010; Relyea, 2005; Pleasants & Oberhauser, 2013). Reductions in photosynthetic microorganisms compromise oxygen production and nutrient cycling, while resistant cyanobacteria may proliferate, causing harmful algal blooms (Márquez et al., 2017).

Although glyphosate degrades faster in water than in soil, recurrent runoff ensures continuous exposure, posing ongoing risks to aquatic biodiversity and ecosystem stability (Annett etal., 2014). These ecological disruptions have downstream effects on human communities that rely on freshwater resources.

3.5 Ecological and Public Health Concerns

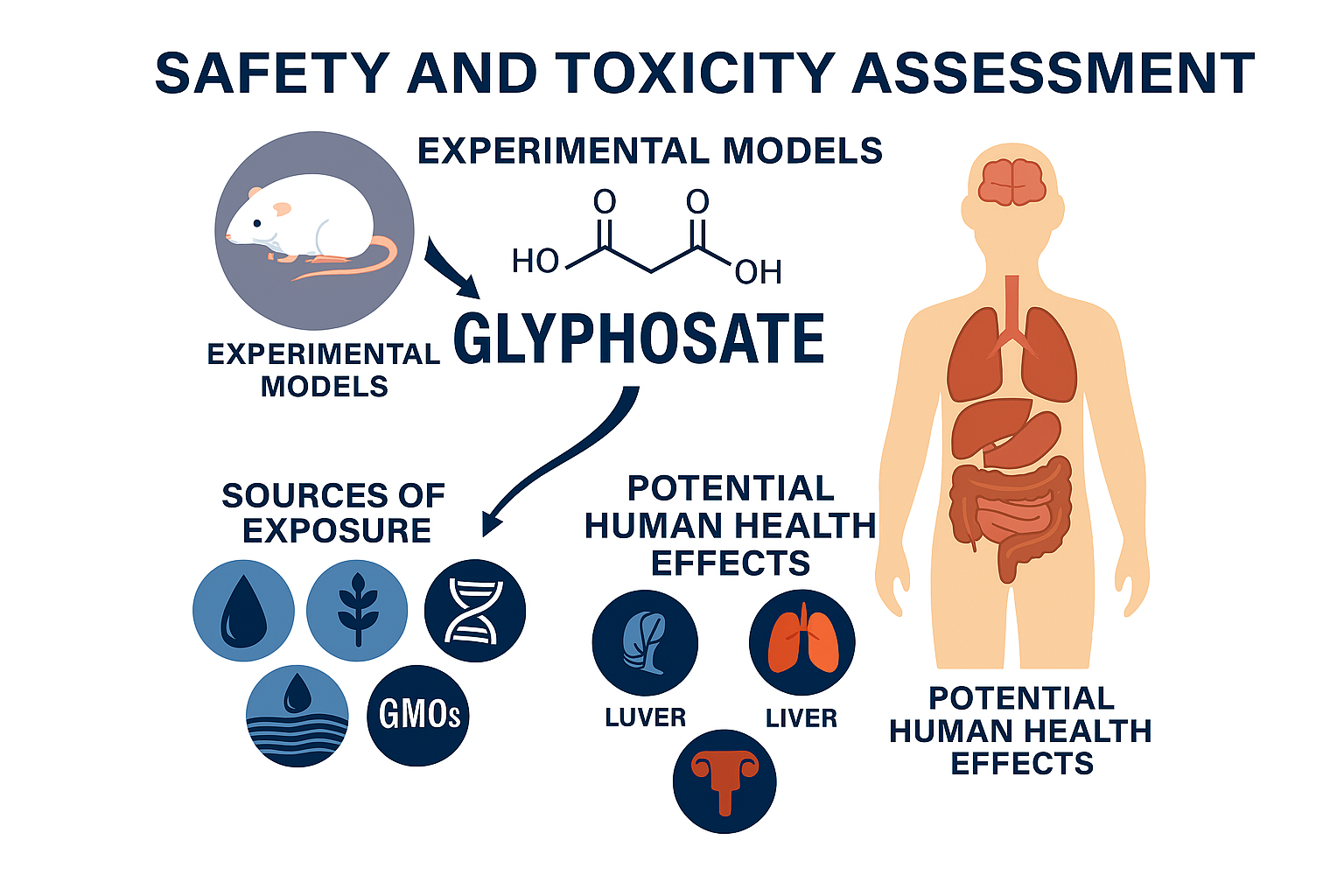

Collectively, glyphosate’s impacts on soil, gut, and aquatic microbiomes raise serious ecological and health concerns. Soil microbial disruption threatens crop resilience and food security; gut dysbiosis compromises metabolic and immune function; and aquatic disturbances reduce biodiversity and water quality (Mason et al., 2012; Benbrook, 2016). These effects are often subtle and cumulative, complicating regulatory assessments that emphasize acute toxicity rather than chronic ecological shifts (Figure 3). As illustrated in Figure 3, glyphosate exposure follows interconnected environmental and biological pathways that translate cumulative, low-dose contact into multi-system health risks often overlooked by conventional toxicity assessments.

Public health debates are further complicated by potential carcinogenicity. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans” in 2015, highlighting the need to integrate microbiome-focused evidence into risk assessments (Guyton et al., 2015).

Figure 3: The potential sources of exposure to glyphosate and possible adverse effects in humans. Safety and Toxicity Assessment of Glyphosate—Conceptual Pathway from Exposure to Potential Health Effects. This schematic summarizes the major components used in evaluating glyphosate’s safety and toxicity. Center: the glyphosate molecule anchors the framework. Left (Experimental Models): icons depict in vivo animal studies and human cell-culture assays commonly used to characterize dose–response, mechanism of action, and hazard classification. Lower left (Sources of Exposure): representative pathways include contaminated water, agricultural application to crops, genetically engineered systems/GMOs, and environmental runoff, indicating routes by which glyphosate can enter human or ecological compartments. Right (Potential Human Health Effects): a human silhouette highlights organ systems frequently examined in risk assessments—brain (neurological), lungs (respiratory), liver (hepatic), gastrointestinal tract, and reproductive organs. Arrows denote the conceptual flow: external exposure ? internal dose ? biological response ? measurable health endpoints. (Courtesy of image from (Williams et al., 2016).

3.6 Gaps in Literature and Research Directions

Research conducted prior to 2018 largely emphasized herbicidal properties and acute toxicity, overlooking glyphosate’s indirect effects on microbial systems (Mesnage & Antoniou, 2017). Many studies were short-term and conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, limiting their ecological relevance (Van Bruggen et al., 2018).

Future investigations should employ longitudinal, field-based studies to capture cumulative effects across ecosystems. Interdisciplinary approaches integrating soil science, microbiology, toxicology, and public health are essential for a holistic understanding of glyphosate’s impacts. Sustainable agricultural practices—such as crop diversification, reduced pesticide dependency, and non-chemical weed management—should also be explored to mitigate ecological and human health risks (Zobiole et al., 2011; Neves et al., 2019) (Table 2). As summarized in Table 2, pre-2018 research on glyphosate largely focused on short-term, laboratory-based studies emphasizing acute toxicity, leaving significant gaps in understanding its long-term, cumulative effects on soil, gut, and aquatic microbiomes. Addressing these gaps through interdisciplinary, field-based, and longitudinal studies is essential to capture ecological and health impacts comprehensively and to inform sustainable agricultural and regulatory practices.

Table 2: Research Gaps in Glyphosate Studies (Pre-2018 Literature)

|

Domain

|

Current Focus of Studies

|

Identified Gaps

|

Future Research Needs

|

|

Soil Systems

|

Short-term effects, crop yield studies

|

Long-term soil fertility impacts, interactions with other agrochemicals

|

Longitudinal field studies on cumulative effects

|

|

Human Health

|

Acute toxicity, exposure thresholds

|

Chronic low-dose impacts on gut microbiome and immune function

|

Clinical and epidemiological studies integrating microbiome science

|

|

Aquatic Systems

|

Laboratory-based toxicity tests

|

Ecosystem-level effects of glyphosate runoff

|

Holistic assessments of aquatic biodiversity and nutrient cycling

|

|

Regulatory Evaluation

|

Toxicological safety assessments

|

Overlooked microbiome disruptions

|

Incorporation of microbiome analysis into herbicide regulation

|