3.1 Bacteria as Biocontrol Agents

Bacteria have been applied to soil, seeds, roots, and other planting structures for many years to enhance plant growth and development. The primary aim of bacterial inoculants is to strengthen beneficial processes such as nitrogen fixation, degradation of toxic chemicals, promotion of plant growth, and the biological suppression of pathogenic microorganisms (Babalola, 2010; Abbasi et al., 2014). Many bacterial genera, including Acinetobacter, Agrobacterium, Alcaligenes, Arthrobacter, Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Bacillus, Bradyrhizobium, Frankia, Pantoea, Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Serratia, Stenotrophomonas, Streptomyces, and Thiobacillus, are currently being evaluated for their potential as biological control agents (Babalola, 2010; Al-Ani et al., 2012). Numerous plant diseases, including nematode infestations and fungal and bacterial infections, have been targeted by these bacteria, often with promising results.

The effectiveness of bacterial biocontrol can vary depending on host plants, soil organisms, and environmental factors. Integrated approaches combining crop rotation, organic soil amendments, and biological management alongside nematicides are considered practical strategies for managing plant-parasitic nematodes (Khan et al., 2023; Hussain et al., 2017). For instance, Pseudomonas species culture filtrates have been reported to suppress the juvenile stages of Meloidogyne javanica under in vitro conditions, demonstrating the potential of bacterial metabolites in nematode management (Berry et al., 2014). Bacterial treatments have also been shown to reduce root galling, nematode populations, and improve plant development and yield (Khan et al., 2023; Das et al., 2010). Certain bacterial genera, including Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, and Bacillus, produce metabolites that interfere with nematode feeding, behavior, and reproduction, thereby reducing root penetration and associated damage (Zhou et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2013). Several studies have demonstrated the practical use of bacterial isolates in managing root-knot nematodes. For example, strains of Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and P. striata have been effective in suppressing nematode populations (Zhang et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2009). Endophytic bacteria such as Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus spp. can induce systemic resistance in host plants by enhancing the activity of defense-related enzymes such as phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), peroxidase, and polyphenol oxidase. These bacteria also secrete antagonistic compounds and modify root exudates, including polysaccharides and amino acids, contributing to disease suppression (Abbasi et al., 2014; Ongena & Jacques, 2008). In tomato crops, the application of P. fluorescens isolates has been reported to activate plant defense enzymes against root-knot nematodes, significantly reducing nematode populations in both soil and roots (Hu et al., 2014; Lamont et al., 2017).

In addition to nematode management, bacterial biocontrol has shown effectiveness in reducing postharvest fungal infections in fruits and vegetables, which contribute to significant yield losses globally. Postharvest losses due to fungal phytopathogens can account for more than 50% of fruit production in certain regions (Zhang et al., 2017). Chemical fungicides, although commonly used, raise concerns regarding environmental pollution, human health, and residual toxicity (Babalola, 2010; Bonaterra et al., 2012). Biological control using bacteria offers an eco-friendly alternative for suppressing phytopathogens while preserving plant and soil health. Biocontrol agents provide multiple benefits, including minimizing causal pathogen populations, enhancing plant protection, reducing contamination of soil and water, and avoiding chemical waste management issues (Berry et al., 2014; Ghazanfar et al., 2016) (Table 2).

Table 2. Fungal strains reported as biocontrol agents against plant pathogenic microbes

|

Fungal strains

|

Test Plant/Disease

|

Target pathogen

|

|

Aspergillus fumigates

|

Cocoa/black pod

|

Phytophthora Palmivora

|

|

Penicillium oxalicum

|

Tomato/wilt

|

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Lycopersici

|

|

Penicillium sp. EU0013

|

Tomato and cabbage/wilt

|

Fusarium oxysporum

|

|

Trichoderma asperellum

|

Beans

|

S. sclerotiorum apothecia

|

|

Trichoderma harzianum

|

Rice/brown spot

|

Bipolaris oryzae

|

|

Trichoderma virens

|

Okra/Root-knot disease

|

Meloidogyne incognita

|

Synthetic postharvest treatments frequently lead to resistance in pathogens, soil degradation, and environmental contamination. As a result, there is a global push toward safer, biologically based alternatives that are effective, ecologically sound, and economically feasible (Babalola, 2010; Bonaterra et al., 2012). In this context, bacterial biocontrol agents such as Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Rhizobium spp. are increasingly valued for their ability to suppress pathogens, improve crop yields, and maintain sustainable agricultural practices (Al-Ani et al., 2012; Arguelles-Arias et al., 2009; Berry et al., 2014).

3.2 Fungi as Biocontrol Agents

Fungi are another major group of biological control agents with significant potential to suppress plant pathogens. Genera such as Trichoderma, Paecilomyces, and Gliocladium have been extensively studied for their antagonistic activity against fungal pathogens like Alternaria, Pythium, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, Phytophthora, Botrytis, Pyricularia, and Gaeumannomyces (Bonaterra et al., 2012; Zhang & Zhang, 2009). Trichoderma spp. act as functional mycoparasites and have been used in field and greenhouse trials to control soil-borne and aerial pathogens (Harman et al., 2004; Lamont et al., 2017).

Nematophagous fungi have also demonstrated efficacy against root-knot nematodes such as Meloidogyne enterolobii. Formulations of Paecilomyces lilacinus have been shown to reduce nematode populations in soil while enhancing crop yield, particularly in tomato, okra, and capsicum (Kiriga et al., 2018; Rao, 2007). Egg-parasitic fungi like P. lilacinus and Pochonia chlamydosporia act directly on nematode eggs, penetrating eggshells with hyphal growth to inhibit reproduction (Kiss, 2003; Verma et al., 2009).

Fungal biocontrol agents can produce nematicidal compounds, including viridin from Trichoderma spp., gliotoxin and acetic acid from T. longibrachiatum and T. virens, and cyclosporine from T. polysporum, which contribute to pathogen suppression (Watanabe et al., 2004; Anitha & Murugesan, 2005; Li et al., 2007). Combinations of bacterial and fungal BCAs, such as Bacillus firmus with Paecilomyces lilacinus, have shown synergistic effects, maximizing nematode control and improving plant growth parameters (Anastasiadis et al., 2008; Bontempo et al., 2017).

Over 30 genera and 80 species of fungi are known to parasitize nematodes and suppress root-knot diseases. Specific soil fungi, including Gliocladium, Penicillium citrinum, and Trichoderma virens, have demonstrated antagonistic activity against pathogens like Colletotrichum falcatum and other fungal infections, further supporting their role as BCAs (Kiss, 2003; Zhang & Zhang, 2009). The ecological advantage of fungal biocontrol lies in its ability to reduce chemical inputs while enhancing soil microbial diversity and plant resilience (Bonaterra et al., 2012; Pieterse et al., 2014).

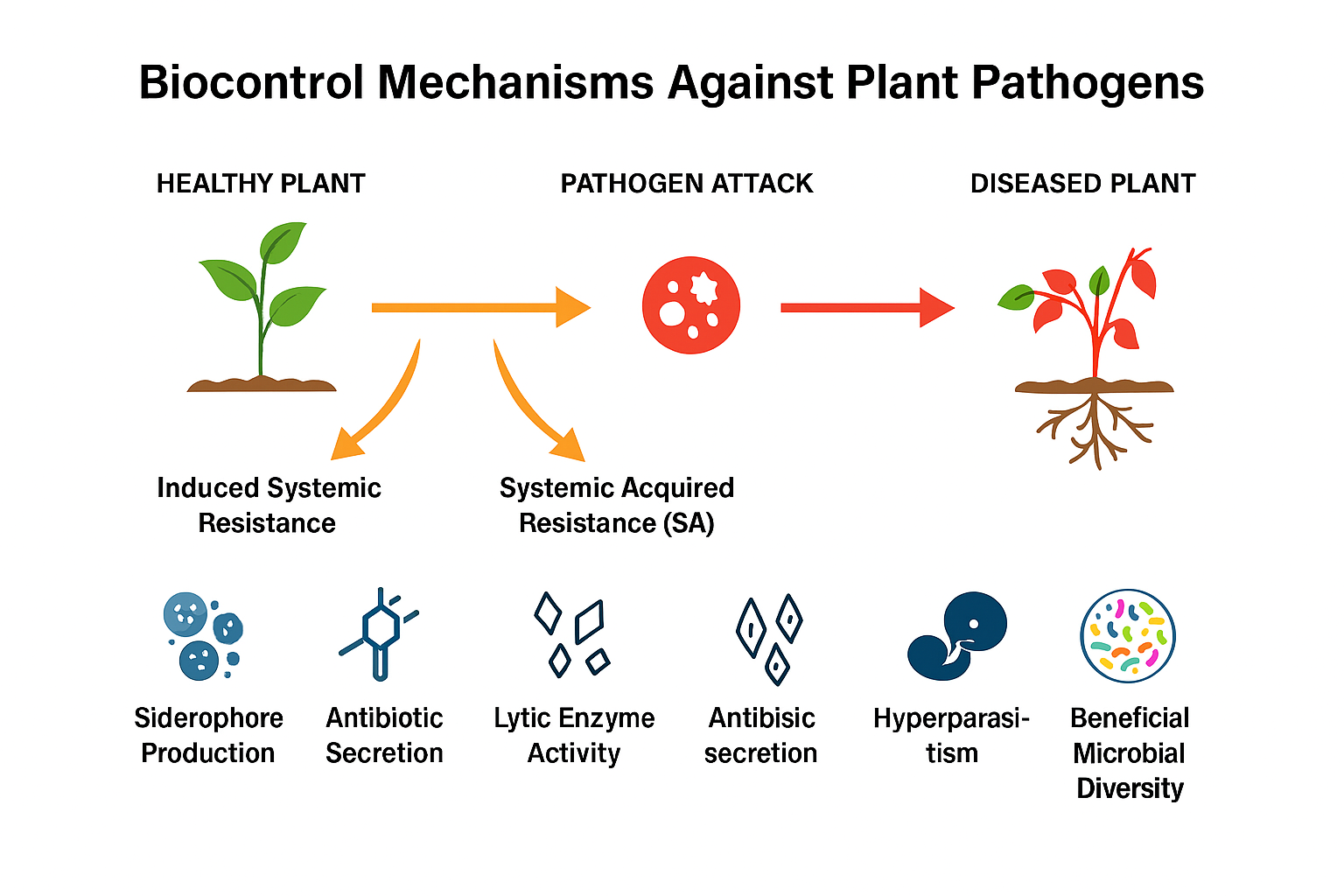

3.3 Mechanisms of Biocontrol

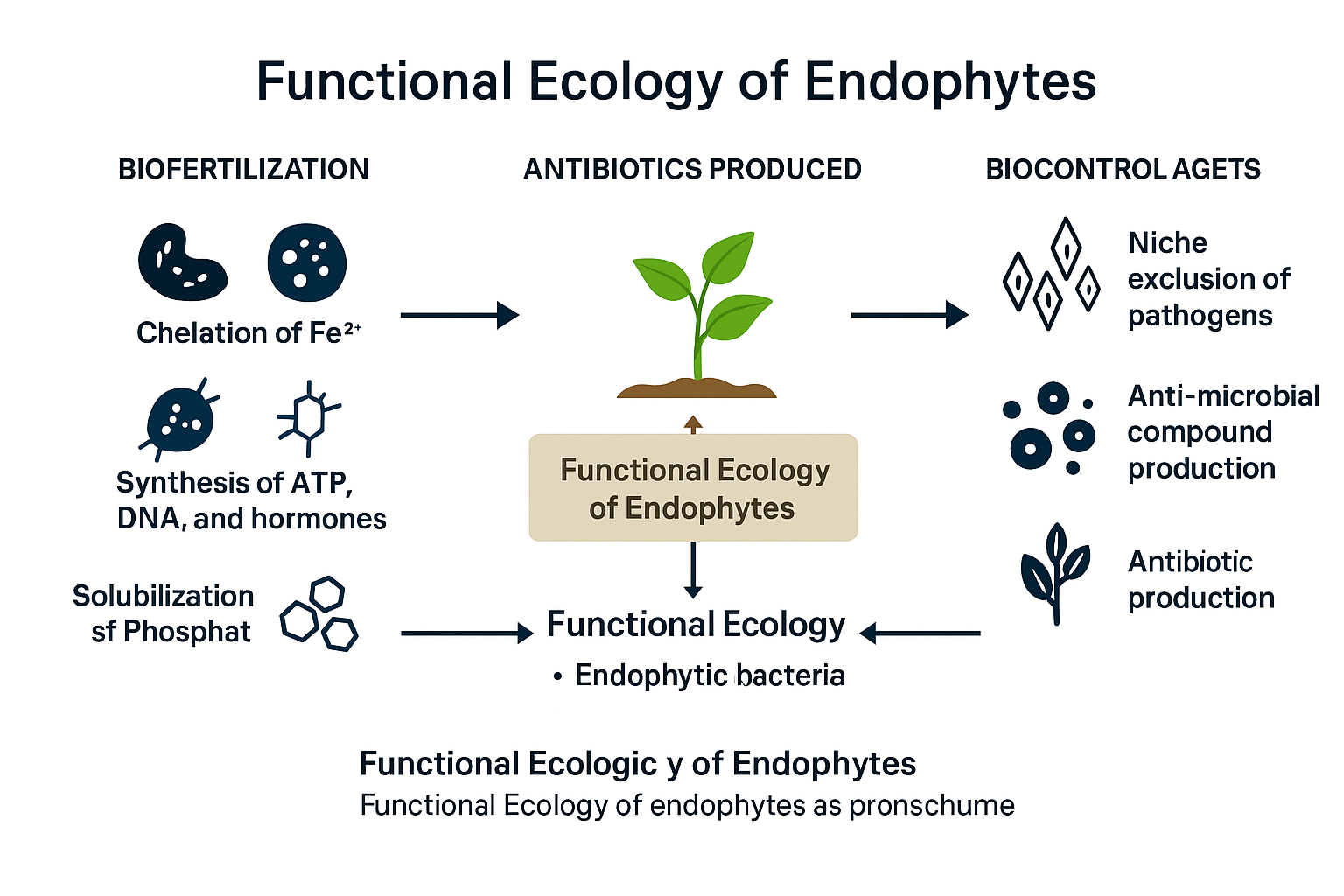

The mechanisms of biocontrol involve multiple interactions between BCAs and plant pathogens. Key processes include the production of hydrolytic enzymes, antibiosis, competition for nutrients such as iron, mycoparasitism, rhizosphere competence, and the induction of systemic resistance in host plants (Haas & Keel, 2003; Bais et al., 2006). Bacteria and fungi secrete secondary metabolites, including antibiotics, siderophores, and volatile compounds, which inhibit pathogen growth and enhance plant immunity (Arguelles-Arias et al., 2009; Ongena & Jacques, 2008).

Understanding these mechanisms is essential for optimizing the application of BCAs in agriculture. Factors such as soil type, microbial community composition, environmental conditions, and host plant compatibility influence the efficacy of BCAs. Advances in formulation, genetic improvement, and delivery systems are improving the consistency and scalability of microbial biocontrol (Lamont et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017).

Overall, bacteria and fungi remain the most extensively studied BCAs, with proven potential to suppress nematodes, fungal pathogens, and postharvest diseases. Their integration into crop management systems offers a sustainable approach to enhancing plant health, reducing chemical dependence, and promoting environmentally friendly agricultural practices (Abbasi et al., 2014; Bonaterra et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017).

3.4 Antibiosis

Many bacterial species produce toxic compounds that are inhibitory or lethal to pathogenic microbes, providing a significant advantage for plant growth and development (Abbasi et al., 2014; Babalola, 2010). Antibiotics are microbial metabolites capable of killing or suppressing other microorganisms even at low concentrations. These compounds are often secondary metabolites synthesized during the idiophase, a stage of growth in which nutrient depletion and high cell density occur, whereas bacterial growth is maximal during the trophophase (de Kievit et al., 2011; Ongena & Jacques, 2008). Antibiosis is considered one of the primary mechanisms through which biocontrol bacteria suppress plant pathogens. By producing antibiotics, bacteria can inhibit pathogen germination, growth, and proliferation, often without direct competition for space or nutrients (Raaijmakers & Mazzola, 2012; Berry et al., 2014). The effectiveness of antibiosis in the rhizosphere depends on the ability of bacterial strains to produce sufficient antibiotic concentrations in their micro-niche on the root surface (Al-Ani et al., 2012; Abbasi et al., 2014).

3.5 Production of Antibiotics by Biocontrol Bacteria

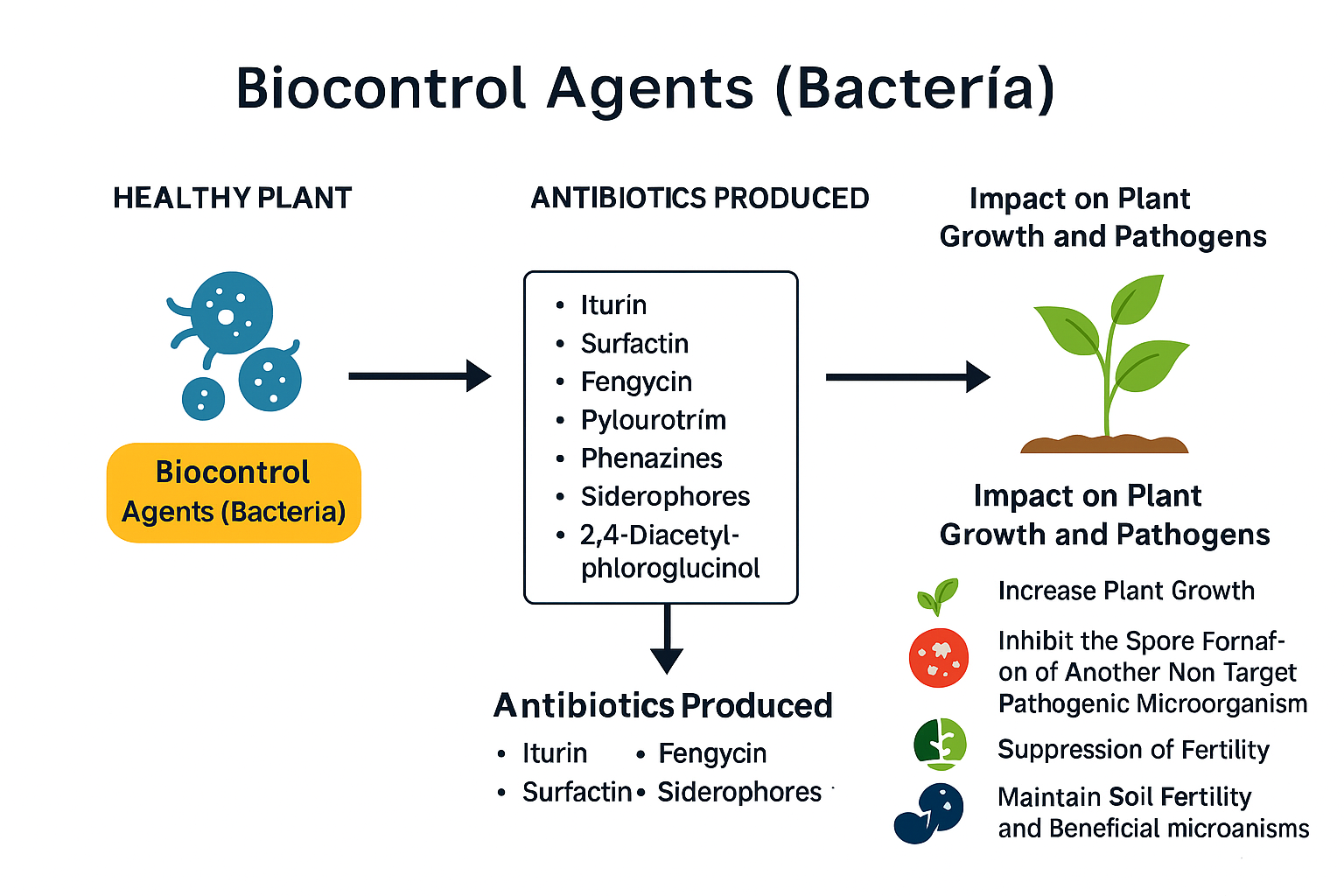

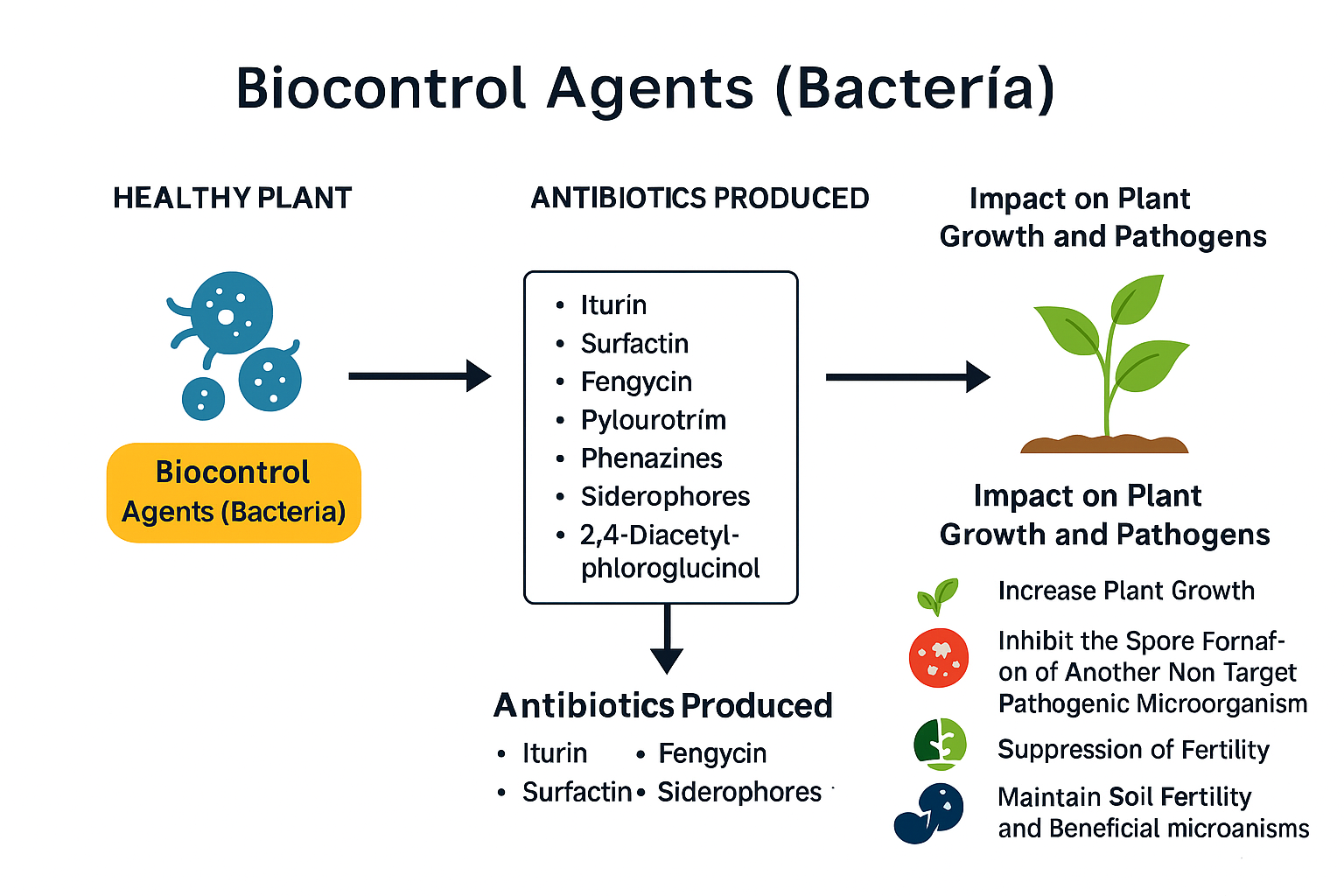

The capacity of bacteria to produce antibiotics is crucial for their biocontrol activity. Actinomycetes, bacteria, and fungi are known to generate a large number of antimicrobial compounds, with approximately 8,700, 2,900, and 4,900 antibiotics, respectively, identified to date (Bérdy, 2005). In biocontrol applications, bacterial isolates such as Bacillus spp. and Pseudomonas spp. have been extensively studied for their production of lipopeptides and antibiotic metabolites. For example, Bacillus species synthesize lipopeptides like iturin, surfactin, and fengycin, which exhibit strong antifungal properties, while Pseudomonas species produce compounds such as 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG), pyrrolnitrin, and phenazine (Ongena & Jacques, 2008; Raaijmakers & Mazzola, 2012). This integrated mode of action highlights how compounds such as iturin, surfactin, fengycin, and phenazines function not only as antimicrobial agents but also as key drivers of sustainable plant protection strategies (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Antibiotics production by bacterial biocontrol agents and their impact on plant growth and other pathogenic microorganism. Mode of action of bacterial biocontrol agents in plant protection and growth promotion. The simplified schematic shows the left-to-right flow: Biocontrol Agents (Bacteria) produce key antimicrobial and competitive factors—such as iturin, surfactin, fengycin, phenazines, siderophores, and 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol—which collectively act on plant–pathogen systems. The right panel summarizes principal outcomes: suppression of pathogenic microorganisms, inhibition of spore formation, enhancement of plant growth traits, and maintenance of soil fertility through support of beneficial microbiota. The diagram employs a clean, vector-based style and a muted academic color palette for journal publication.

These bacterial metabolites act directly on pathogens by inhibiting spore germination or growth. Pseudomonas spp. produces a variety of antimicrobial compounds, including hydrogen cyanide, phenazines, pyoluteorin, siderophores, and proteases, which interfere with fungal cell integrity and metabolic activity (Compant et al., 2010; Berry et al., 2014). Enzymes secreted by these bacteria, such as chitinase, cellulase, proteases, and ß-glucanase, further contribute to antifungal activity by degrading cell walls of pathogenic fungi (Hernandez-Leon et al., 2015; Abbasi et al., 2014).

Peptides, particularly lipopeptides, represent a major class of bacterial antibiotics. These are synthesized either ribosomally or non-ribosomally and are predominantly produced by Bacillus species. While the production of secondary metabolites is sometimes considered outside the classical definition of biocontrol—which emphasizes the use of living organisms to suppress pathogens—the ecological function of these metabolites is integral to bacterial antagonism against pathogens in situ (Glare et al., 2012; Berry et al., 2014). In practical applications, these metabolites are used to limit the impact of harmful microorganisms in an environmentally safe manner, reinforcing their significance as biological control tools (Abbasi et al., 2014; Babalola, 2010).

3.6 Production of Antibiotics by Fungal Antagonists

Fungal biocontrol agents, particularly Trichoderma spp., are widely distributed in soils and produce a broad spectrum of volatile and nonvolatile antimicrobial compounds (Harman et al., 2004; Zhang & Zhang, 2009). Volatile compounds include alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, hydrogen cyanide, and ethylene, which inhibit pathogen growth, while nonvolatile substances, including peptides, limit the mycelial development of pathogenic fungi.Several antifungal metabolites produced by fungi have been documented. For instance, Gliocladium virens produces gliotoxin, gliovirin, heptelidic acid, valinomycin, viridiol, and viridin, which exhibit broad-spectrum activity against soil-borne pathogens such as Rhizoctonia solani, Pythium debaryanum, Pythium aphanidermatum, Macrophomina phaseolina, and Sclerotium rolfsii (Singh et al., 2005; Bonaterra et al., 2012). The production of these metabolites enables fungi to suppress plant pathogens both in the rhizosphere and postharvest environments, highlighting their utility in integrated disease management strategies (Harman et al., 2004; Zhang & Zhang, 2009).

Fungal antagonists also employ mechanisms similar to bacterial BCAs, including direct parasitism of pathogens, secretion of lytic enzymes, and competition for nutrients. The combination of metabolite production and physical interactions enhances the efficacy of fungal biocontrol agents, particularly in soil ecosystems where multiple pathogens coexist (Abbasi et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017). These attributes make fungal BCAs indispensable tools for sustainable agriculture, offering environmentally friendly alternatives to chemical fungicides while maintaining crop health and productivity.

Table 2. Fungal strains reported as biocontrol agents against plant pathogenic microbes

|

Fungal strains

|

Test Plant/Disease

|

Target pathogen

|

|

Aspergillus fumigates

|

Cocoa/black pod

|

Phytophthora Palmivora

|

|

Penicillium oxalicum

|

Tomato/wilt

|

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Lycopersici

|

|

Penicillium sp. EU0013

|

Tomato and cabbage/wilt

|

Fusarium oxysporum

|

|

Trichoderma asperellum

|

Beans

|

S. sclerotiorum apothecia

|

|

Trichoderma harzianum

|

Rice/brown spot

|

Bipolaris oryzae

|

|

Trichoderma virens

|

Okra/Root-knot disease

|

Meloidogyne incognita

|