1. Introduction

Viruses are now recognized as the most abundant biological entities on Earth, outnumbering cellular life across nearly all ecosystems—from the open oceans to extreme habitats such as permafrost and hot springs (Paez-Espino et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2019). They exert profound influence on microbial communities, ecosystem functioning, and global biogeochemical cycles. Historically, viral research was constrained by culture-dependent techniques, which required co-cultivation of viruses with their cellular hosts. However, such methods provided only a limited view of viral diversity because the vast majority of viruses remain uncultivable. The advent of viral metagenomics has transformed this field by enabling direct sequencing of viral nucleic acids from environmental samples, thereby bypassing the cultivation bottleneck (Edwards & Rohwer, 2005; Breitbart et al., 2002).

Studies in extreme environments have revealed remarkable viral genetic diversity and complexity, offering insights into viral adaptation and evolution. Extremophiles—organisms capable of surviving in high salinity, acidity, temperature, or radiation—serve as hosts for diverse viruses that exhibit unique structural and genetic traits (Paez-Espino et al., 2016; Roux et al., 2019). Because viruses require living hosts for replication, their interactions shape host population dynamics, influence microbial diversity, and alter host genomes through horizontal gene transfer (Brüssow et al., 2004; Thingstad, 2000). These interactions are particularly consequential in extreme environments, where viruses regulate microbial development and contribute indirectly to global biogeochemical cycles, including carbon and nutrient turnover (Suttle, 2007; Weitz et al., 2018). Yet, despite their ecological importance, knowledge of viral diversity and prevalence in extreme habitats remains limited (Emerson et al., 2018; Roux et al., 2016).

The rise of metagenomics offers unprecedented opportunities to explore viromes—the total viral genetic content of a habitat. Unlike conventional virology, which focuses on isolated viruses, metagenomics provides a community-wide perspective, uncovering novel viral sequences and functions (Breitbart et al., 2002; Mokili et al., 2012). Many newly discovered viral sequences have no homologues in existing databases, underscoring the extent of “viral dark matter” (Roux et al., 2019; Pratama et al., 2021). This has major implications not only for understanding viral diversity but also for identifying novel proteins, enzymes, and bioactive molecules with potential biotechnological and medical applications (Guo et al., 2021).

Marine environments provide striking examples of viral abundance and influence. Estimates suggest that a milliliter of seawater can contain up to 15,000 viral genotypes (Suttle, 2007; Brum & Sullivan, 2015). These viruses regulate bacterial populations through infection and lysis, thereby controlling microbial community structure and driving nutrient recycling. Viral lysis releases dissolved organic matter, fueling microbial food webs and influencing global carbon cycling (Weinbauer, 2004; Roux et al., 2016). Similarly, soil viromes are now being revealed through metagenomics. Soil viruses, estimated at 107 to 108 particles per gram, modulate plant-microbe interactions and affect nutrient cycling processes, which has direct implications for agriculture and land management (Emerson et al., 2018; Starr et al., 2019).

Human-associated viromes also exemplify the ecological and biomedical significance of viral metagenomics. The human gut virome is dominated by bacteriophages, which influence microbiome composition and may modulate susceptibility to diseases, including Clostridium difficile infections and inflammatory disorders (Ott et al., 2017; Duerkop & Hooper, 2013). Discoveries such as crAssphage—one of the most abundant viruses in the human gut—highlight the power of metagenomics to uncover key viral players previously hidden from view (Díaz-Muñoz, 2019). These findings bridge ecology and medicine, demonstrating how viral ecology can inform human health and disease management (Monaco et al., 2016).

Despite rapid advances in sequencing technologies, challenges remain. Viral genomes are highly diverse, with small sizes, unusual structures, and rapid evolutionary rates, complicating assembly and classification (Pratama et al., 2021; Roux et al., 2019). Moreover, sampling bias persists, as much of Earth’s virome—especially from extreme environments—remains underexplored (Paez-Espino et al., 2016; Wommack & Colwell, 2000). Integrating multi-omics approaches—combining viral metagenomics with metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and single-virus genomics—holds promise for resolving functional roles of viruses across ecosystems (Brum & Sullivan, 2015; Gregory et al., 2016).

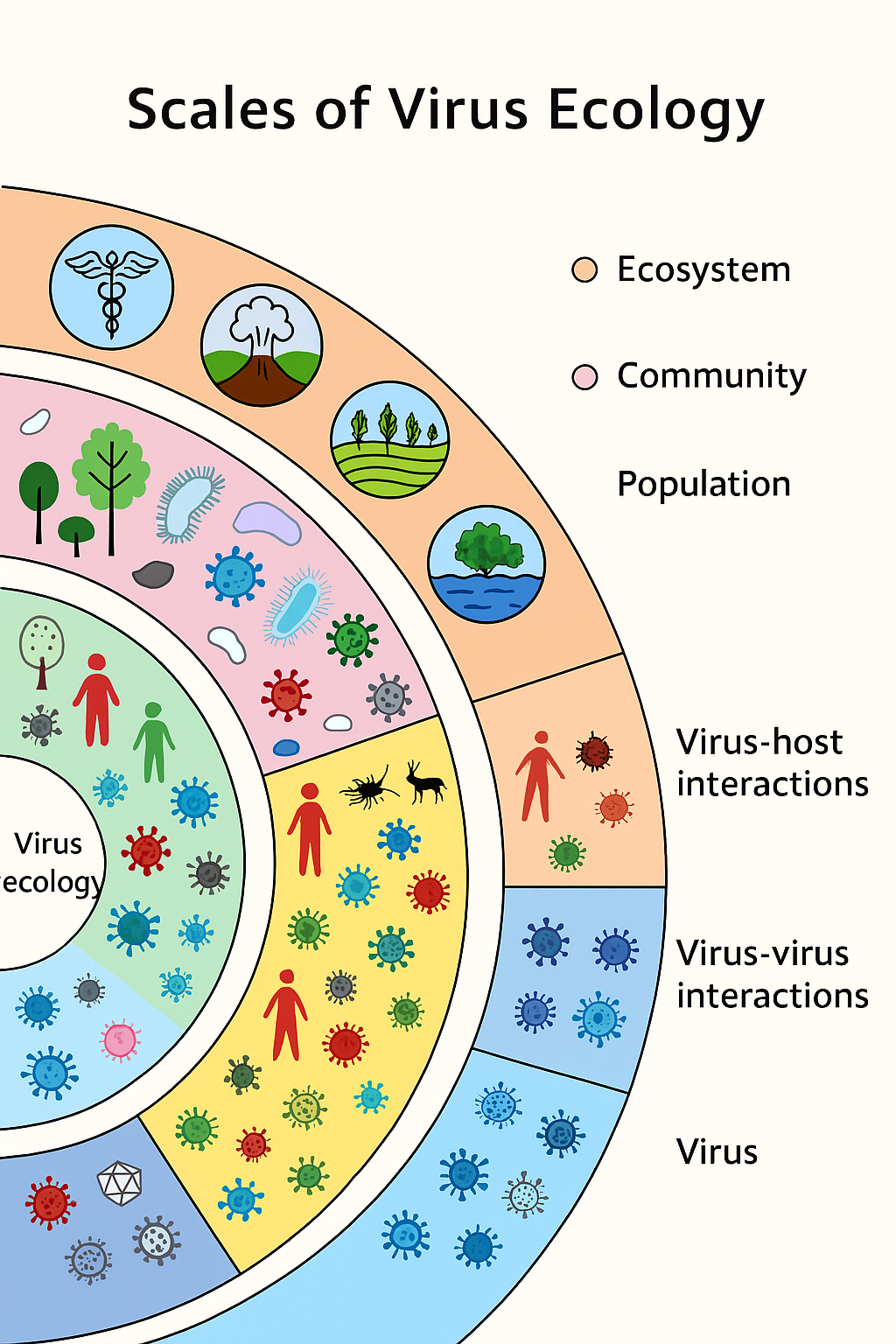

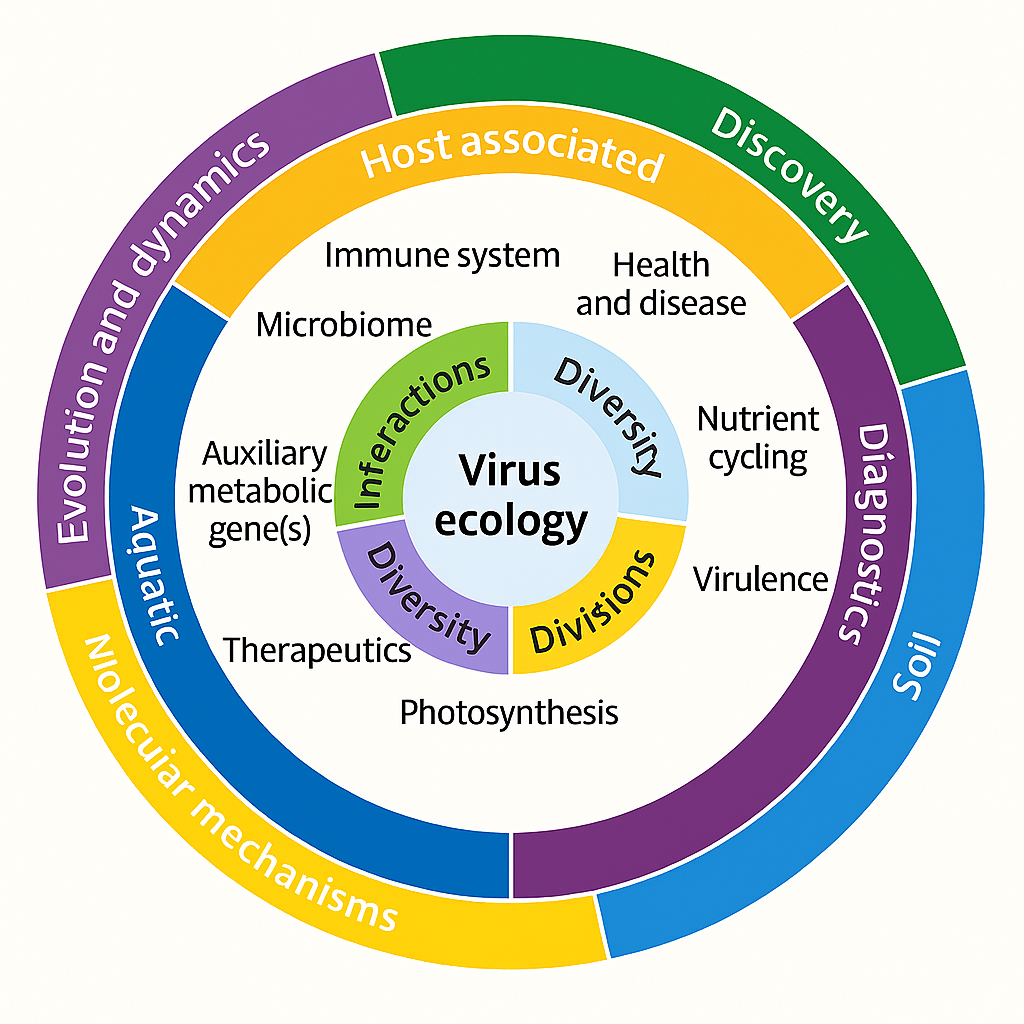

Viral metagenomics has revolutionized virology by revealing the immense, previously hidden diversity of viruses and their roles in microbial ecology. By applying an ecological framework, researchers can better understand viral diversity, distribution, and interactions, as well as their consequences for ecosystem stability, global nutrient cycles, and human health (Roux et al., 2016; Hurwitz et al., 2013). This introduction sets the stage for examining how viral metagenomics contributes to our understanding of microbial community dynamics in both natural and host-associated ecosystems, with a special emphasis on extreme environments. An ecological framework illustrating how viral metagenomics integrates viral diversity, distribution, host interactions, and ecosystem-level processes across environmental and host-associated systems is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of virus ecology illustrating key components: interactions, diversity, dynamics, and distributions. The outer ring highlights major research domains such as evolution, host association, aquatic systems, soil ecology, and molecular mechanisms, while the inner ring emphasizes functional aspects including immune system, microbiome, nutrient cycling, photosynthesis, and virulence.

The primary objectives of this research are to investigate the diversity and composition of viral populations across marine, soil, and human-associated ecosystems using metagenomic approaches, providing a comprehensive understanding of viral community structures in distinct environments. It also aims to analyze how viruses influence microbial community dynamics and regulate key biogeochemical processes, thereby contributing to ecosystem functioning and nutrient cycling. Furthermore, the study seeks to evaluate the potential ecological and health implications of virome diversity, with particular attention to extreme environments and host-associated microbiomes where viral interactions may play crucial roles in maintaining ecological balance and impacting host health.