1. Introduction

Omics technologies have transformed the landscape of biological and medical research by providing comprehensive, high-throughput data on the molecular composition and regulation of cells, tissues, and organisms (Horgan & Kenny, 2011; Karahalil, 2016; Beale et al., 2016). These technologies include genomics, which examines DNA sequences and structural variations; transcriptomics, which profiles RNA expression patterns; proteomics, which assesses protein abundance, modifications, and interactions; and metabolomics, which evaluates small-molecule metabolites in biological systems (Johnson et al., 2016; Pinu et al., 2019). Collectively, omics approaches enable holistic insights into biological processes, bridging the gap between genotype, phenotype, and environmental influences (Gómez-Cebrián et al., 2021; Karahalil, 2016).

The rapid evolution of next-generation sequencing (NGS) and mass spectrometry has greatly enhanced the sensitivity, throughput, and resolution of omics studies (Dopazo, 2014; Tiew et al., 2023). In genomics, high-throughput sequencing allows the detection of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), copy number variations, and structural variants across large populations, facilitating genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and personalized medicine applications (Swinney, 2014; Malcangi et al., 2023). Transcriptomics, using RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), captures gene expression dynamics across tissues, time points, and disease states, enabling identification of regulatory networks and alternative splicing events (Ma et al., 2019; O’Rourke et al., 2020). Proteomics leverages mass spectrometry and protein microarrays to map protein abundance, post-translational modifications, and protein-protein interactions, providing functional insights beyond gene expression alone (Fernández-Acero et al., 2019). Metabolomics focuses on small molecules that reflect cellular metabolic states, offering a direct readout of physiological and pathological processes (Johnson et al., 2016; Pinu et al., 2019).

Despite technological advancements, variability in omics data remains a major challenge (Bolyen et al., 2019; Janiszewska et al., 2022). Differences in sample preparation, platform selection, data processing, and normalization strategies can introduce technical noise and bias, complicating cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses (Beale et al., 2016; Secco et al., 2025). Biological variability—including age, sex, genetic background, diet, and microbiome composition—further contributes to heterogeneity, emphasizing the importance of rigorous experimental design, replication, and statistical analysis (Francine, 2022; Nogueira & Botelho, 2021). Reviews and meta-analyses of omics studies are therefore critical to synthesize findings, quantify effect sizes, assess heterogeneity, and identify potential biases (Secco et al., 2025).

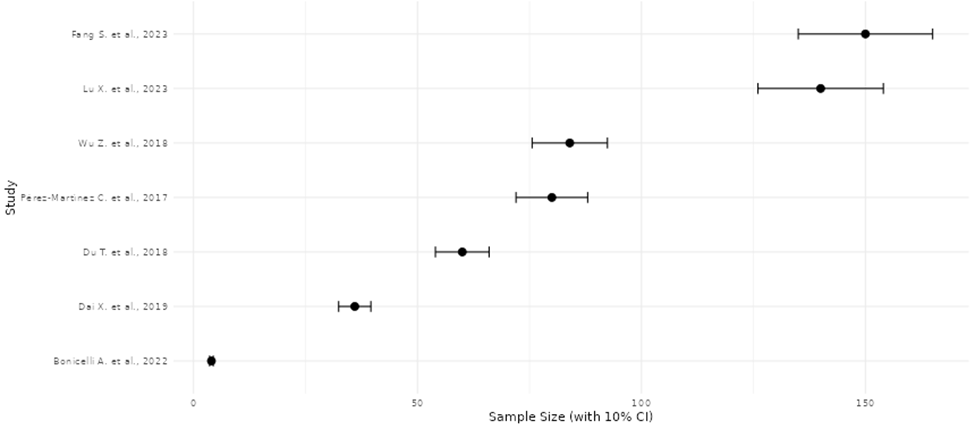

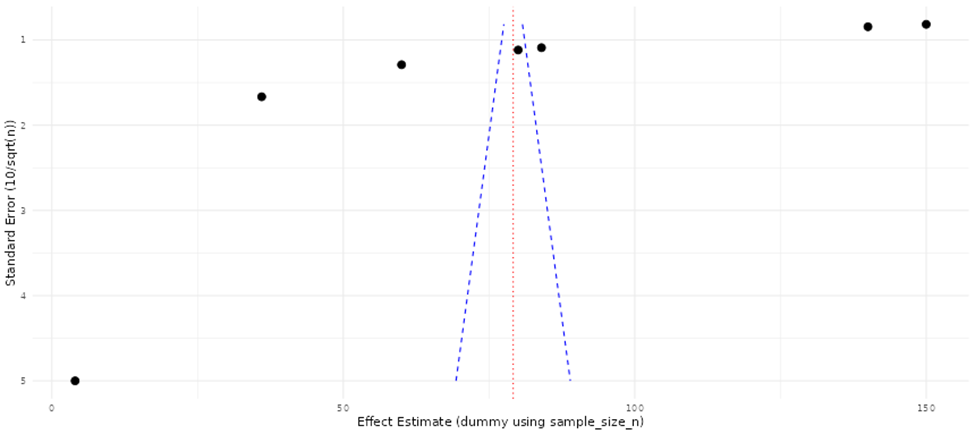

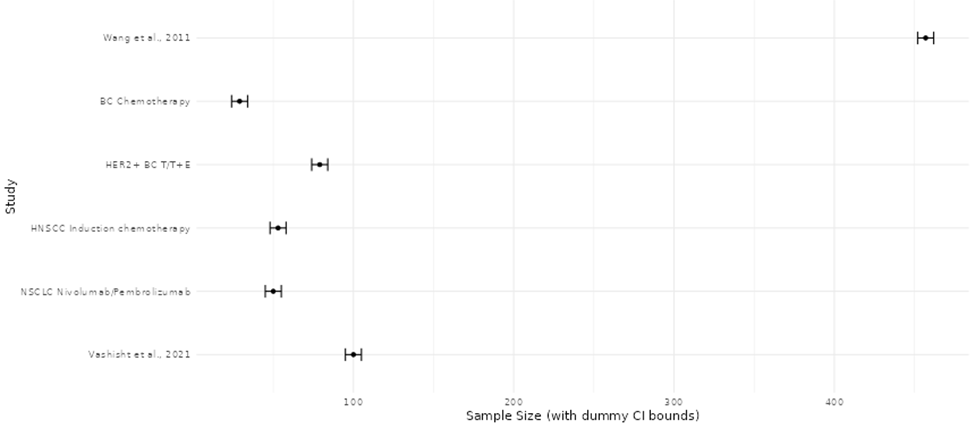

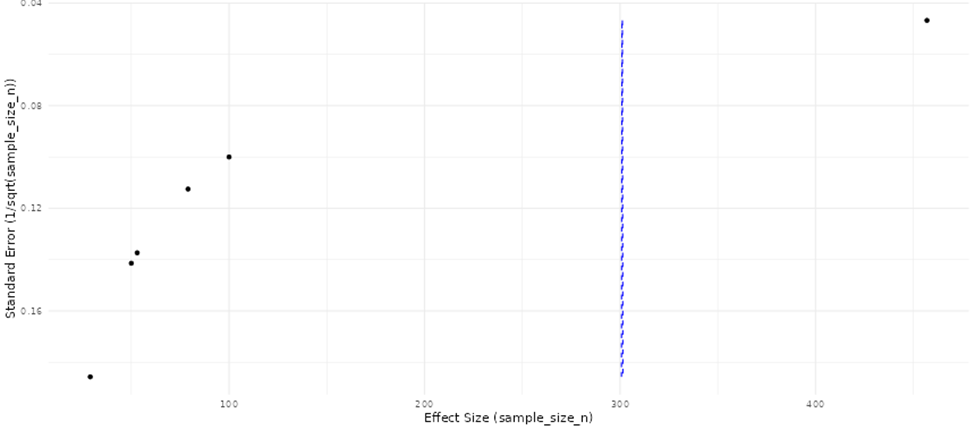

Comparative visualization and summary analyses were applied to evaluate the consistency, magnitude, and reliability of reported molecular effects across omics studies (Beale et al., 2016). Study-level effect estimates were examined collectively to identify concordant trends in direction and strength of molecular changes, allowing assessment of agreement across datasets generated using diverse platforms and experimental designs. Patterns in effect magnitude relative to study size and analytical rigor were also evaluated to detect potential imbalances in the published literature, including the overrepresentation of smaller studies reporting pronounced effects. These integrative assessments facilitated identification of reproducible biomarkers, pathway-level signatures, and recurring molecular patterns, while simultaneously revealing methodological sources of variability. The findings highlight the need for harmonized analytical pipelines and standardized reporting practices to improve cross-study comparability and strengthen biological inference in omics research. (Beale et al., 2016; Pinu et al., 2019).

Omics approaches have significantly advanced understanding in multiple disease contexts (Dopazo, 2014; Tiew et al., 2023). In oncology, genomics and transcriptomics have uncovered driver mutations, gene expression signatures, and regulatory networks that inform prognosis and targeted therapies (Swinney, 2014). Proteomic and metabolomic profiling has revealed dysregulated signaling pathways, metabolic rewiring, and potential therapeutic targets in cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disorders (Johnson et al., 2016; Malcangi et al., 2023). Integrative multi-omics analyses, combining genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, have enabled the construction of comprehensive molecular networks, facilitating systems-level understanding of complex diseases (Pinu et al., 2019).

The clinical translation of omics findings depends on validation, reproducibility, and standardization (Malcangi et al., 2023; Tiew et al., 2023). Cross-platform and cross-cohort validation ensures that biomarkers and molecular signatures are reliable across populations and technical conditions. Rigorous statistical modeling, including multivariate analyses, machine learning approaches, and network-based inference, is essential for handling high-dimensional omics data and avoiding overfitting (Bolyen et al., 2019). Additionally, ethical considerations—such as informed consent, data privacy, and equitable access—must be addressed when implementing omics in personalized medicine (Malcangi et al., 2023).

This review aims to consolidate current evidence on omics methodologies, evaluating their accuracy, reproducibility, and clinical relevance (Beale et al., 2016; Secco et al., 2025). By synthesizing data across studies, the review identifies trends in biomarker discovery, pathway analysis, and multi-omics integration, while quantifying heterogeneity and potential biases. The findings highlight the promise of omics for advancing precision medicine, identifying therapeutic targets, and elucidating mechanisms of disease, while underscoring the technical and methodological challenges that must be overcome for reliable clinical application (Ayon, 2023; Gaudêncio et al., 2023; Goff et al., 2020).

Overall, omics approaches represent a paradigm shift in modern biology and medicine, enabling holistic characterization of molecular systems and advancing personalized healthcare (Horgan & Kenny, 2011; Karahalil, 2016; Handelsman, 2009; Pereira, 2019; Liu et al., 2010; Cunha et al., 2019; Fitzpatrick & Walsh, 2016). ). This work provides critical insights into the strengths, limitations, and future directions of omics research, guiding both experimental design and clinical translation