Adusumilli, P. S., Cherkassky, L., Villena-Vargas, J., Colovos, C., Servais, E., Plotkin, J., Jones, D. R., & Sadelain, M. (2014). Regional delivery of mesothelin-targeted CAR T cell therapy generates potent and long-lasting CD4-dependent tumor immunity. Science Translational Medicine, 6(261). https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3010162

Adusumilli, P. S., Zauderer, M. G., Riviere, I., Solomon, S. B., Rusch, V. W., O’Cearbhaill, R. E., Zhu, A., Cheema, W., Chintala, N. K., Halton, E., et al. (2021). A phase I trial of regional mesothelin-targeted CAR T-cell therapy in patients with malignant pleural disease, in combination with the anti-PD-1 agent pembrolizumab. Cancer Discovery, 11(11), 2748–2763. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0407

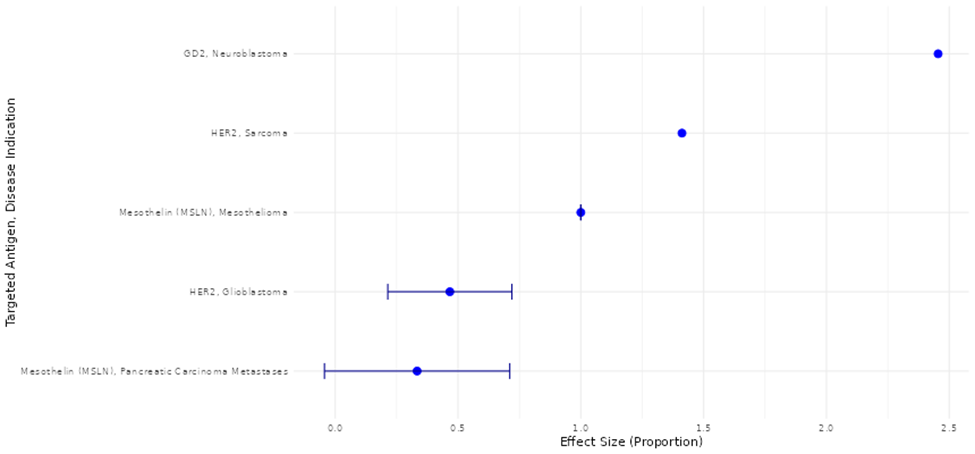

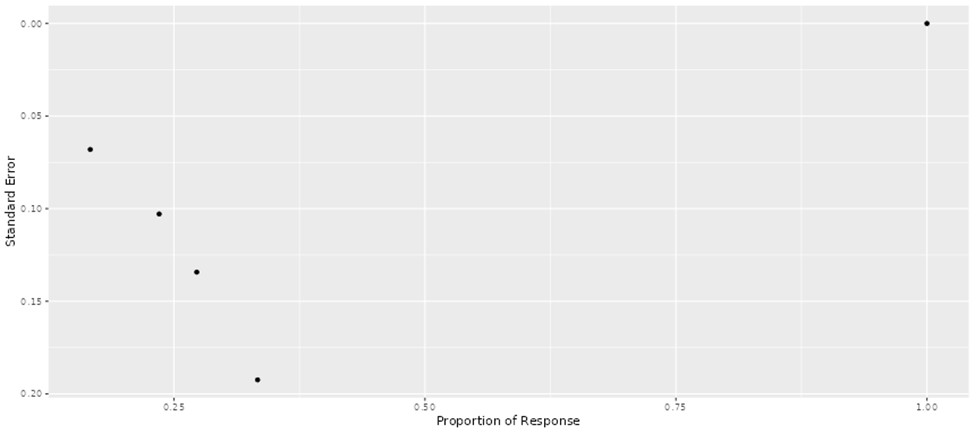

Ahmed, N., Brawley, V. S., Hegde, M., Bielamowicz, K., Kalra, M., Landi, D., … Gottschalk, S. (2017). HER2-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified virus-specific T cells for progressive glioblastoma: A phase 1 dose-escalation trial. JAMA Oncology, 3(8), 1094–1101. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0184

Ahmed, N., Brawley, V. S., Hegde, M., Robertson, C., Ghazi, A., Gerken, C., … Gottschalk, S. (2015). Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the immunotherapy of HER2-positive sarcoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(15), 1688–1696. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.0225

Andreou, T., Neophytou, C., Mpekris, F., & Stylianopoulos, T. (2025). Expanding immunotherapy beyond CAR T cells: Engineering diverse immune cells to target solid tumors. Cancers, 17(17), 2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172917

Arndt, C., Feldmann, A., Koristka, S., Schäfer, M., Bergmann, R., Mitwasi, N., Berndt, N., Bachmann, D., Kegler, A., Schmitz, M., et al. (2019). A theranostic PSMA ligand for PET imaging and retargeting of T cells expressing the universal chimeric antigen receptor UniCAR. OncoImmunology, 8(10), 1659095. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2019.1659095

Bagley, S. J., Logun, M., Fraietta, J. A., Wang, X., Desai, A. S., Bagley, L. J., Nabavizadeh, A., Jarocha, D., Martins, R., Maloney, E., et al. (2024). Intrathecal bivalent CAR T cells targeting EGFR and IL13Rα2 in recurrent glioblastoma: Phase 1 trial interim results. Nature Medicine, 30(5), 1320–1329. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02893-z

Beatty, G. L., O’Hara, M. H., Lacey, S. F., Torigian, D. A., Nazimuddin, F., Chen, F., Kulikovskaya, I. M., Soulen, M. C., McGarvey, M., Nelson, A. M., … June, C. H. (2018). Activity of mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells against pancreatic carcinoma metastases in a phase 1 trial. Gastroenterology, 155(1), 29–32. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.029

Bielamowicz, K., Fousek, K., Byrd, T. T., Samaha, H., Mukherjee, M., Aware, N., Wu, M.-F., Orange, J. S., Sumazin, P., Man, T.-K., et al. (2018). Trivalent CAR T cells overcome interpatient antigenic variability in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology, 20(4), 506–518. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox182

Birkholz, K., Hombach, A., Krug, C., Reuter, S., Kershaw, M., Kampgen, E., Schuler, G., Abken, H., Schaft, N., & Dorrie, J. (2009). Transfer of mRNA encoding recombinant immunoreceptors reprograms CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for use in the adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Gene Therapy, 16(5), 596–604. https://doi.org/10.1038/gt.2008.189

Boccalatte, F., Mina, R., Aroldi, A., Leone, S., Suryadevara, C. M., Placantonakis, D. G., & Bruno, B. (2022). Advances and hurdles in CAR T cell immune therapy for solid tumors. Cancers, 14(20), 5108. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14205108

Brentjens, R. J., Davila, M. L., Riviere, I., Park, J., Wang, X., Cowell, L. G., … Sadelain, M. (2013). CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science Translational Medicine, 5(177), 177ra38. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930

Brown, C. E., Alizadeh, D., Starr, R., Weng, L., Wagner, J. R., Naranjo, A., Ostberg, J. R., Blanchard, M. S., Kilpatrick, J., Simpson, J., et al. (2016). Regression of glioblastoma after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(26), 2561–2569. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1610497

Brown, C. E., Badie, B., Barish, M. E., Weng, L., Ostberg, J. R., Chang, W.-C., Naranjo, A., Starr, R., Wagner, J., & Wright, C. (2015). Bioactivity and safety of IL13Rα2-redirected chimeric antigen receptor CD8+ T cells in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Clinical Cancer Research, 21(18), 4062–4072. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0428

Choi, B. D., Gedeon, P. C., Herndon, J. E., II, Archer, G. E., Reap, E. A., Sanchez-Perez, L., Mitchell, D. A., Bigner, D. D., & Sampson, J. H. (2013). Human regulatory T cells kill tumor cells through granzyme-dependent cytotoxicity upon retargeting with a bispecific antibody. Cancer Immunology Research, 1(3), 163. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0049

Choi, B. D., Yu, X., Castano, A. P., Bouffard, A. A., Schmidts, A., Larson, R. C., Bailey, S. R., Boroughs, A. C., Frigault, M. J., Leick, M. B., et al. (2019). CAR-T cells secreting BiTEs circumvent antigen escape without detectable toxicity. Nature Biotechnology, 37(9), 1049–1058. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0192-1

Chung, H., Jung, H., & Noh, J.-Y. (2021). Emerging approaches for solid tumor treatment using CAR-T cell therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(22), 12126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222212126

Di Stasi, A., Tey, S. K., Dotti, G., Fujita, Y., Kennedy-Nasser, A., Martinez, C., Straathof, K., Liu, E., Durett, A. G., Grilley, B., et al. (2011). Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(18), 1673–1683. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1106152

Dudley, M. E., Wunderlich, J. R., Robbins, P. F., Yang, J. C., Hwu, P., Schwartzentruber, D. J., ... & Rosenberg, S. A. (2002). Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science, 298(5594), 850-854.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1076514

Ercilla-Rodriguez, P., Sanchez-Diez, M., Alegria-Aravena, N., Quiroz-Troncoso, J., Gavira-O'Neill, C. E., Gonzalez-Martos, R., & Ramirez-Castillejo, C. (2024). CAR-T lymphocyte-based cell therapies; mechanistic substantiation, applications and biosafety enhancement with suicide genes: new opportunities to melt side effects. Frontiers in Immunology, 15, 1333150. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1333150

Fedorov, V. D., Themeli, M., & Sadelain, M. (2013). PD-1–and CTLA-4–based inhibitory chimeric antigen receptors (iCARs) divert off-target immunotherapy responses. Science translational medicine, 5(215), 215ra172-215ra172. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3006597

Feldmann, A., Arndt, C., Bergmann, R., Loff, S., Cartellieri, M., Bachmann, D., ... & Bachmann, M. (2017). Retargeting of T lymphocytes to PSCA-or PSMA positive prostate cancer cells using the novel modular chimeric antigen receptor platform technology “UniCAR”. Oncotarget, 8(19), 31368. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15572

Feucht, J., Sun, J., Eyquem, J., Ho, Y. J., Zhao, Z., Leibold, J., ... & Sadelain, M. (2019). Calibration of CAR activation potential directs alternative T cell fates and therapeutic potency. Nature medicine, 25(1), 82-88. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0290-5

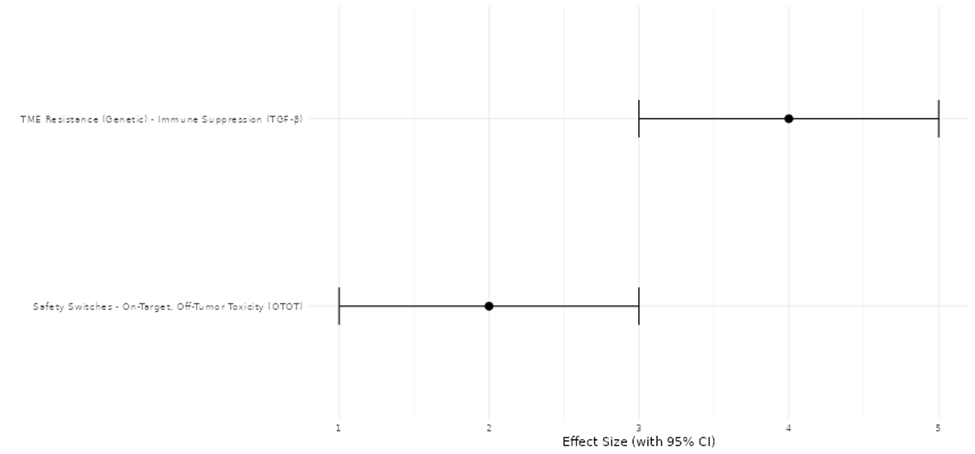

Gwadera, J., Grajewski, M., Chowaniec, H., Gucia, K., Michon, J., Mikulicz, Z., Knast, M., Pujanek, P., Tolkacz, A., Murawa, A., et al. (2025). Can we use CAR-T cells to overcome immunosuppression in solid tumours? Biology, 14(8), 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081035

Hatae, R., Kyewalabye, K., Yamamichi, A., Chen, T., Phyu, S., Chuntova, P., ... & Okada, H. (2024). Enhancing CAR-T cell metabolism to overcome hypoxic conditions in the brain tumor microenvironment. JCI insight, 9(7), e177141. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.177141

Hegde, M., DeRenzo, C. C., Zhang, H., Mata, M., Gerken, C., Shree, A., ... & Ahmed, N. M. (2017). Expansion of HER2-CAR T cells after lymphodepletion and clinical responses in patients with advanced sarcoma. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.10508

Hegde, M., Mukherjee, M., Grada, Z., Pignata, A., Landi, D., Navai, S. A., ... & Ahmed, N. (2016). Tandem CAR T cells targeting HER2 and IL13Rα2 mitigate tumor antigen escape. The Journal of clinical investigation, 126(8), 3036-3052. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI83416

Kershaw, M. H., Westwood, J. A., Parker, L. L., Wang, G., Eshhar, Z., Mavroukakis, S. A., White, D. E., Wunderlich, J. R., Canevari, S., Rogers-Freezer, L., et al. (2006). A phase I study on adoptive immunotherapy using gene-modified T cells for ovarian cancer. Clinical Cancer Research, 12(20), 6106–6115. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1183

Klampatsa, A., Haas, A. R., Moon, E. K., & Albelda, S. M. (2017). Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM). Cancers, 9(9), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers9090115

Lee, D. W., Kochenderfer, J. N., Stetler-Stevenson, M., Cui, Y. K., Delbrook, C., Feldman, S. A., … Mackall, C. L. (2015). T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: A phase 1 dose-escalation trial. The Lancet, 385(9967), 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3

Liao, Q., He, H., Mao, Y., Ding, X., Zhang, X., & Xu, J. (2020). Engineering T cells with hypoxia-inducible chimeric antigen receptor (HiCAR) for selective tumor killing. Biomarker research, 8(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-020-00238-9

Morgan, R. A., Yang, J. C., Kitano, M., Dudley, M. E., Laurencot, C. M., & Rosenberg, S. A. (2010). Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Molecular therapy, 18(4), 843-851. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2010.24

Neelapu, S. S., Locke, F. L., Bartlett, N. L., Lekakis, L. J., Miklos, D. B., Jacobson, C. A., … Go, W. Y. (2017). Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(26), 2531–2544. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1707447

Nguyen, D. T., Ogando-Rivas, E., Liu, R., Wang, T., Rubin, J., Jin, L., Tao, H., Sawyer, W. W., Mendez-Gomez, H. R., Cascio, M., et al. (2022). CAR T cell locomotion in solid tumor microenvironment. Cells, 11(12), 1974. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11121974

O’Rourke, D. M., Nasrallah, M. P., Desai, A., Melenhorst, J. J., Mansfield, K., Morrissette, J. J., ... & Maus, M. V. (2017). A single dose of peripherally infused EGFRvIII-directed CAR T cells mediates antigen loss and induces adaptive resistance in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Science translational medicine, 9(399), eaaa0984.https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0984

Park, J. H., Rivière, I., Gonen, M., Wang, X., Sénéchal, B., Curran, K. J., … Brentjens, R. J. (2018). Long-term follow-up of CD19 CAR therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(5), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709919

Parkhurst, M. R., Yang, J. C., Langan, R. C., Dudley, M. E., Nathan, D. A. N., Feldman, S. A., ... & Rosenberg, S. A. (2011). T cells targeting carcinoembryonic antigen can mediate regression of metastatic colorectal cancer but induce severe transient colitis. Molecular Therapy, 19(3), 620-626.https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2010.272

Picheta, N., Piekarz, J., Danilowska, K., Szklener, K., & Mandziuk, S. (2025). CAR-T in the Treatment of Solid Tumors—A Review of Current Research and Future Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(19), 9486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26199486

Posey, A. D., Schwab, R. D., Boesteanu, A. C., Steentoft, C., Mandel, U., Engels, B., ... & June, C. H. (2016). Engineered CAR T cells targeting the cancer-associated Tn-glycoform of the membrane mucin MUC1 control adenocarcinoma. Immunity, 44(6), 1444-1454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.014

Ramakrishna, S., Highfill, S. L., Walsh, Z., Nguyen, S. M., Lei, H., Shern, J. F., ... & Fry, T. J. (2019). Modulation of target antigen density improves CAR T-cell functionality and persistence. Clinical Cancer Research, 25(17), 5329-5341. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3784

Rojas-Quintero, J., Díaz, M. P., Palmar, J., Galan-Freyle, N. J., Morillo, V., Escalona, D., González-Torres, H. J., Torres, W., Navarro-Quiroz, E., Rivera-Porras, D., et al. (2024). CAR T cells in solid tumors: Overcoming obstacles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(8), 4170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25084170

Schuberth, P. C., Hagedorn, C., Jensen, S. M., Gulati, P., van den Broek, M., Mischo, A., & Petrausch, U. (2013). Treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma by fibroblast activation protein-specific re-directed T cells. Journal of translational medicine, 11(1), 187. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-11-187

Schuster, S. J., Svoboda, J., Chong, E. A., Nasta, S. D., Mato, A. R., Anak, Ö., … Porter, D. L. (2017). Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B-cell lymphomas. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(26), 2545–2554. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1708566

Shin, M. H., Oh, E., Kim, Y., Nam, D.-H., Jeon, S. Y., Yu, J. H., & Minn, D. (2023). Recent advances in CAR-based solid tumor immunotherapy. Cells, 12(12), 1606. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12121606

Smirnov, S., Zaritsky, Y., Silonov, S., Gavrilova, A., & Fonin, A. (2025). Advancing CAR-T Therapy for Solid Tumors: From Barriers to Clinical Progress. Biomolecules, 15(10), 1407. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101407

Vitanza, N. A., Johnson, A. J., Wilson, A. L., Brown, C., Yokoyama, J. K., Künkele, A., ... & Park, J. R. (2021). Locoregional infusion of HER2-specific CAR T cells in children and young adults with recurrent or refractory CNS tumors: an interim analysis. Nature medicine, 27(9), 1544-1552. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01404-8

Wang, L. C. S., Lo, A., Scholler, J., Sun, J., Majumdar, R. S., Kapoor, V., ... & Albelda, S. M. (2014). Targeting fibroblast activation protein in tumor stroma with chimeric antigen receptor T cells can inhibit tumor growth and augment host immunity without severe toxicity. Cancer immunology research, 2(2), 154-166. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0027

Wang, Y., Chen, M., Wu, Z., Tong, C., Dai, H., Guo, Y., Liu, Y., Huang, J., Lv, H., Luo, C., … Han, W. (2018). CD133-directed CAR T cells for advanced metastatic malignancies: A phase I trial. OncoImmunology, 7(7), e1440169. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2018.1440169

Whilding, L. M. (Significant contributor to: Zhou, R., Yazdanifar, M., Roy, L. D., Whilding, L. M., Gavrill, A., Maher, J., & Mukherjee, P. (2019). CAR T cells targeting the tumor MUC1 glycoprotein reduce triple-negative breast cancer growth). Frontiers in Immunology, 10, 1149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01149

White, L. G., Goy, H. E., Rose, A. J., & McLellan, A. D. (2022). Controlling cell trafficking: addressing failures in CAR T and NK cell therapy of solid tumours. Cancers, 14(4), 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14040978