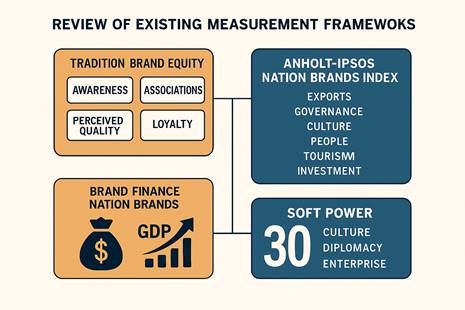

Aaker and Keller conceptualized brand equity as the sum of awareness, associations, perceived quality, and loyalty. These pillars can be adapted to nation branding when integrated with cultural and diplomatic variables. Anholt-Ipsos Nation Brands Index measures perception across exports, governance, culture, people, tourism, and investment. Brand Finance Nation Brands calculate monetary value by linking perception to GDP contribution. Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework for nation brand equity, highlighting four interconnected pillars—awareness, perception, performance, and trust—that collectively shape a nation’s global image. The Soft Power 30 Index evaluates influence through culture, diplomacy, and enterprise. Despite sophistication, these indices rely heavily on perception surveys and secondary data, lacking behavioral validation or longitudinal depth.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework for Nation Brand Equity. This figure illustrates the four interconnected pillars—Awareness, Perception, Performance, and Trust—that collectively define a nation’s brand equity. Positioned around a global core, these dimensions integrate marketing theory with reputation management to capture both perceptual and performance-based indicators of national image.

The traditional brand equity theories created within the marketing field have greatly influenced the measurement of national brand equity. Brand equity is conceptualized as a multifaceted entity made up of brand awareness, brand associations, perceived quality, and brand loyalty in seminal works (Aaker, 1991) and (Keller, 1993). These factors have been adapted to the context of nation branding since they have demonstrated efficacy in evaluating consumer-based brand value. However, nations function inside intricate socio-political, cultural, and diplomatic ecosystems, in contrast to commercial brands.

As a result, academics contend that conventional brand equity models need to be broadened to include factors like international conduct, national identity, government legitimacy, and cultural diplomacy. When appropriately adjusted, awareness can reflect global visibility, associations can capture symbolic national images, perceived quality can match institutional performance and exports, and loyalty can be demonstrated through long-term diplomatic alignment, foreign investment, and repeat travel (Dinnie, 2016; Fan, 2010).

Several global indexes have been developed to operationalize these theoretical concepts at the applied level. One of the most popular frameworks is the Anholt-Ipsos Nation Brands Index (NBI), which gauges attitudes around the world in six areas: exports, governance, culture and heritage, people, tourism, investment, and immigration (Anholt, 2007; Ipsos, 2023). The NBI offers useful comparative insights into how countries are viewed around the world, especially regarding reputation management and soft power. However, issues about cultural bias, respondent familiarity, and the instability of beliefs created by short-term media narratives have been raised by its substantial dependence on perception-based survey data (Kaneva, 2011).

Conversely, the Brand Finance By connecting brand strength rankings to economic metrics including GDP contribution, trade success, and investment attractiveness, the Nation Brands methodology aims to give national brands a monetary value (Brand Finance, 2023). This method provides a more economically grounded evaluation of national brand equity by utilizing ISO 10668 standards for brand value. However, detractors contend that converting perceptual indices into monetary worth runs the risk of oversimplifying the intricate, non-market aspects of a country's image, especially when it comes to aspects like diplomatic legitimacy, cultural impact and trust (Fan, 2010; Dinnie, 2016).

The Soft Power 30 Index, created by Portland Communications, is another significant framework that assesses national influence using a mix of objective measurements and subjective surveys in areas such as culture, diplomacy, education, enterprise, governance, and digital engagement. Although this index advances the field by combining reputational indicators with institutional performance, it is still limited by a lack of direct behavioral validation, such as long-term shifts in migration patterns, investment flows, or foreign policy alignment (McClory, 2019).

Existing nation branding frameworks have similar problems despite their methodological complexity. The majority only provide a picture of the country's reputation at a certain moment in time and primarily rely on secondary data sources and cross-sectional perception surveys. There is a continual discrepancy between assessed image and real-world impact since few systematically account for behavioral results or long-term trust creation. This drawback highlights the need for more dynamic, empirically supported measurement models that incorporate behavioral, economic, and perceptual aspects throughout time.