1.Introduction

Environmental pollution has emerged as one of the most pressing global challenges of the 21st century. Rapid industrialization, urban expansion, intensive agriculture, and improper waste management practices have led to the continuous release of a wide range of pollutants into the environment. Contaminants such as heavy metals, petroleum hydrocarbons, synthetic dyes, pesticides, and pharmaceutical residues have increasingly been detected in soil, freshwater, and marine ecosystems (Singh, 2006). These pollutants not only disrupt ecological balance but also pose significant risks to human health, including carcinogenic, mutagenic, and endocrine-disrupting effects. The persistence and recalcitrance of many of these compounds make their removal particularly challenging, emphasizing the urgent need for innovative, sustainable, and cost-effective remediation strategies.

Traditional remediation approaches, such as chemical oxidation, thermal treatment, soil washing, and incineration, have been widely applied to address environmental contamination. While effective in certain contexts, these methods often come with significant drawbacks. Chemical treatments can produce hazardous byproducts, thermal methods consume high energy and generate greenhouse gases, and physical removal strategies may transfer pollutants from one medium to another without complete detoxification (Harms et al., 2011). Furthermore, the high operational costs and technical complexity of conventional methods limit their feasibility, particularly in developing regions where industrial pollution is most acute. These limitations have prompted researchers to explore biological approaches, which leverage the natural abilities of microorganisms to detoxify and transform pollutants in situ.

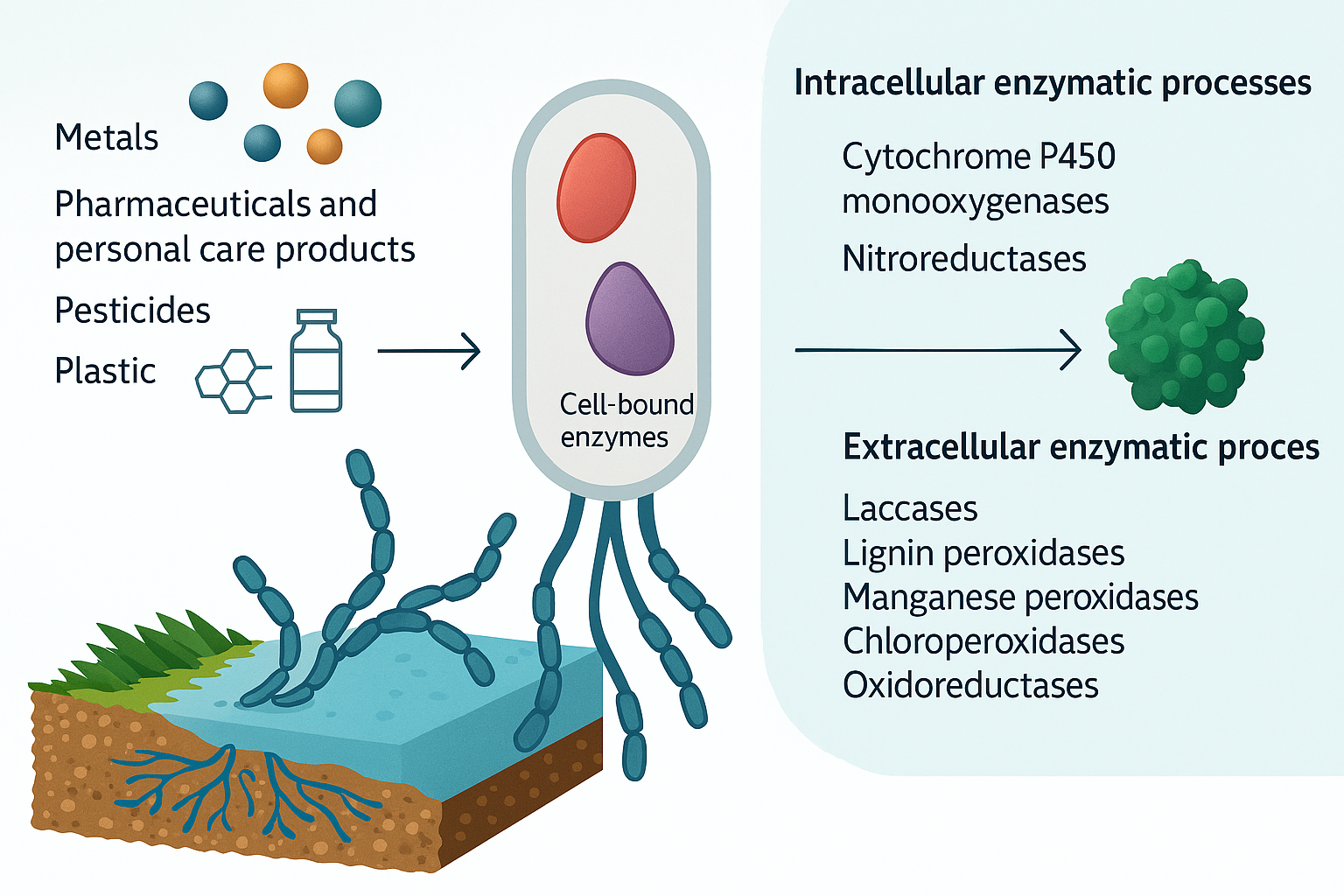

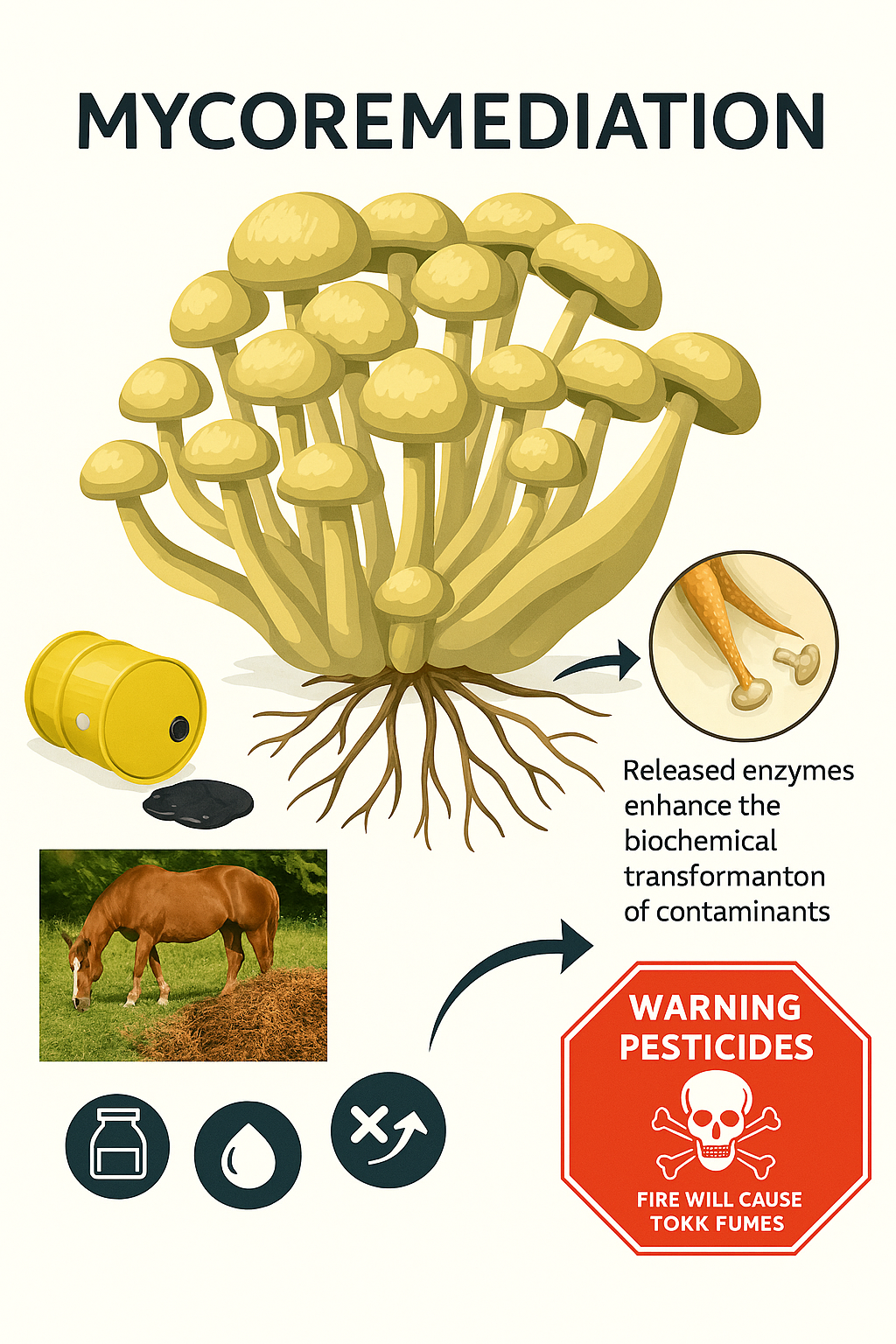

Among biological strategies, fungal bioremediation, or mycoremediation, has gained remarkable attention over the past few decades. Fungi occupy a unique ecological niche, capable of decomposing complex organic matter in natural environments. Their metabolic versatility allows them to transform a wide spectrum of pollutants into less harmful or non-toxic forms (Pointing, 2001). Unlike bacteria, which generally rely on intracellular enzymatic processes, fungi possess powerful extracellular enzymatic systems capable of degrading large and complex molecules. This distinction enables fungi to tackle recalcitrant compounds such as lignin, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), synthetic dyes, and various pharmaceutical residues that often resist bacterial degradation (Leonowicz et al., 1999).

White-rot fungi, including Phanerochaete chrysosporium and Trametes versicolor, have been particularly studied for their ligninolytic enzyme systems. Enzymes such as lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, and laccase allow these fungi to break down highly stable aromatic compounds, effectively reducing their environmental toxicity (Martínez et al., 2005). The extracellular nature of these enzymes offers a unique advantage: pollutants do not need to enter fungal cells to be degraded. This capability is especially significant for soil and water treatment, where pollutants may be bound to particulate matter or present in complex matrices. In addition to enzymatic degradation, fungi exhibit several other mechanisms that enhance their potential as bioremediation agents. Fungal cell walls are rich in polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids that serve as binding sites for heavy metals, enabling biosorption and bioaccumulation processes. This ability has been widely documented in species such as Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Rhizopus, which have demonstrated significant uptake of lead, cadmium, mercury, and other metal ions from contaminated soils and effluents (Gadd, 2009; Anand et al., 2006). The dual functionality of fungi—degrading organic pollutants and sequestering inorganic contaminants—positions mycoremediation as a versatile and comprehensive approach for environmental detoxification. Despite its promise, several challenges must be addressed to fully harness the potential of mycoremediation. Fungal growth and activity are highly sensitive to environmental factors such as temperature, pH, moisture content, and nutrient availability. Additionally, the effectiveness of fungal degradation can be influenced by the chemical structure and concentration of pollutants, as well as competition with native microbial communities. Large-scale application of fungal bioremediation also faces logistical hurdles, including the cultivation and distribution of fungal biomass, maintenance of optimal growth conditions in contaminated sites, and monitoring of degradation efficacy over time. Nevertheless, ongoing advances in biotechnology, genetic engineering, and environmental engineering are gradually overcoming these barriers. For example, the development of immobilized fungal systems, enzyme enhancement techniques, and fungal consortia tailored for specific pollutants has expanded the practical applicability of mycoremediation.

The ecological and economic benefits of fungal bioremediation further underscore its relevance in contemporary environmental management. Unlike chemical or physical methods, mycoremediation is inherently sustainable, often requiring minimal energy input and generating limited secondary waste. Fungi can thrive in diverse environments, including soils, sediments, industrial effluents, and aquatic systems, offering flexible solutions across multiple sectors. Moreover, fungal biomass post-treatment can be repurposed, for instance, as biofertilizer or soil amendment, adding value to the remediation process and supporting circular economy principles. The growing body of literature documenting successful pilot-scale and field applications attests to the practical viability of fungi as eco-friendly agents for environmental restoration.

Given the mounting challenges of pollution and the limitations of conventional remediation techniques, there is an increasing imperative to explore alternative strategies that are both effective and environmentally sustainable. Mycoremediation stands out as a promising candidate, offering unique mechanisms for pollutant degradation, heavy metal sequestration, and ecosystem restoration. By elucidating the enzymatic pathways, biosorption capacities, and environmental adaptability of fungi, researchers can develop optimized systems for targeted pollutant removal, paving the way for broader adoption of fungal-based remediation technologies.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of mycoremediation, examining the underlying mechanisms, applications, and current challenges associated with fungal-based pollutant removal. Through an integrative discussion of enzymatic degradation, biosorption, bioaccumulation, and emerging biotechnological approaches, we highlight the potential of fungi to address a range of environmental contaminants. By situating mycoremediation within the broader context of sustainable environmental management, this work underscores its significance as a cost-effective, versatile, and ecologically responsible strategy for mitigating pollution on a global scale.