The demographic characteristics of the surveyed households provide a foundational understanding of the population under study (Table 1). Among the 270 individuals surveyed, males comprised 55.56% and females 44.44%, indicating a slightly higher representation of men. The age distribution reveals a relatively young population, with children aged 1–14 years constituting 25.93% and young adults aged 14–34 years making up 27.78% of respondents. Adults aged 35–55 years account for 23.15%, whereas those between 56–64 years represent 13.89%. Elderly individuals aged 65 years and above form the smallest group at 9.26%. This age structure reflects a dynamic community with a significant proportion of children and working-age adults, suggesting potential implications for labor availability, household responsibilities, and health needs. Marital status data show that just over half of respondents (50.93%) are married, while 45.37% are unmarried, and a minor proportion (3.70%) are divorced or widowed. This distribution suggests relative social stability and the presence of family-based support systems, which can influence household decision-making, economic activities, and the adoption of safety or health practices. In terms of health, an overwhelming majority (95.37%) reported no illness, with only 3.70% living with chronic conditions and less than 1% (0.93%) being handicapped. This indicates generally favorable health conditions among respondents, which could impact their work capacity and resilience. Religiously, all 50 surveyed households identified as Muslim, highlighting cultural and religious homogeneity, which may influence community norms, labor expectations, and health practices. Overall, the demographic profile portrays a young, healthy, family-oriented, and culturally cohesive population, offering essential context for interpreting subsequent findings (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic Profile of Survey Respondents:

|

Demographic Profile

|

Details

|

Total Household Member of the Respondents

|

Percentage (%)

|

|

Total Population

|

Male

|

150

|

55.56

|

|

Female

|

120

|

44.44

|

|

Total

|

270

|

100.00

|

|

Age

|

1 to 14

|

70

|

25.93

|

|

14-34

|

75

|

27.78

|

|

35-55

|

62

|

23.15

|

|

56-64

|

38

|

13.89

|

|

65+

|

25

|

9.26

|

|

Total

|

270

|

100.00

|

|

Marital status

|

Married

|

138

|

50.93

|

|

Unmarried

|

122

|

45.37

|

|

Divorced/Widow

|

10

|

3.70

|

|

Total

|

270

|

100.00

|

|

Health status

|

No Disease

|

257

|

95.37

|

|

Handicapped

|

3

|

0.93

|

|

Chronic

|

10

|

3.70

|

|

Total

|

270

|

100.00

|

|

Religion by HH

|

Muslim

|

50

|

100.00

|

|

Hindu

|

0

|

0.00

|

|

Total

|

50

|

100.00

|

The economic profile of households, as captured in Table 2, illustrates both the income distribution and the underlying gender disparities. Among the 50 respondents considered for income analysis, 55% reported a household income of up to 20,000 BDT. Within this group, women slightly outnumber men, accounting for 30% versus 25%, reflecting greater female representation in the lowest-income category. This may indicate limited access to higher-paying employment for women or greater economic dependency on household income. The second-largest group, representing 35% of respondents, reported household incomes between 20,001 and 30,000 BDT, and all of these individuals were men, demonstrating a pronounced gender imbalance in attaining moderately higher income levels. Similarly, 10% of respondents earned between 30,001 and 40,000 BDT, again exclusively men. The absence of women in these higher brackets underscores structural inequities in income opportunities, which could result from socio-cultural norms, restricted mobility, or limited participation in formal employment. Overall, men represented 70% of the total respondents in the income analysis, with women at 30%, suggesting that men play a more prominent role in income generation, whereas women are more likely to be economically dependent. These findings reveal that a majority of households fall within the lowest income bracket, highlighting economic vulnerability and the necessity for inclusive labor policies and empowerment initiatives (Table 2).

Table 2. Income Level

|

Income Level

|

Male

|

Percentage (%)

|

Female

|

Percentage (%)

|

Total

|

Percentage (%)

|

|

Up to 20,000

|

13

|

25.00

|

15

|

30

|

27

|

55.00

|

|

20,001 to 30,000

|

18

|

35.00

|

0

|

0

|

18

|

35.00

|

|

30,001 to 40,000

|

5

|

10.00

|

0

|

0

|

5

|

10.00

|

|

Total

|

36

|

70.00

|

15

|

30

|

50

|

100.00

|

Table 3. Local Housing Condition

|

SN

|

Type of Housing

|

No.

|

%

|

|

1

|

Semi- pucca

|

10

|

20.00

|

|

2

|

Tin made

|

25

|

50.00

|

|

3

|

Kutcha

|

15

|

30.00

|

|

|

Total

|

50

|

100.00

|

Housing conditions, an essential indicator of living standards and socio-economic status, were also assessed (Table 3). Among the 50 households surveyed, 50% resided in tin-made houses. While commonly used in rural and semi-urban areas, these structures provide only moderate protection against adverse weather and are susceptible to long-term wear. This prevalence indicates that a significant portion of the community lives in modest, temporary accommodations. Additionally, 30% of households live in kutcha houses, which are constructed from natural materials like mud, bamboo, or thatch. These homes offer minimal protection against environmental challenges such as heavy rainfall or flooding, reflecting economic constraints and vulnerability. Semi-pucca houses, representing 20% of the sample, combine permanent materials such as brick walls with temporary roofs and provide more durability than kutcha houses, yet remain below the standard of fully pucca housing. Collectively, these findings underscore that the majority of households live in basic structures, highlighting a pressing need for sustainable housing interventions to enhance resilience and safety (Table 3).

3.1 Opportunities and Fair Treatment of Workers

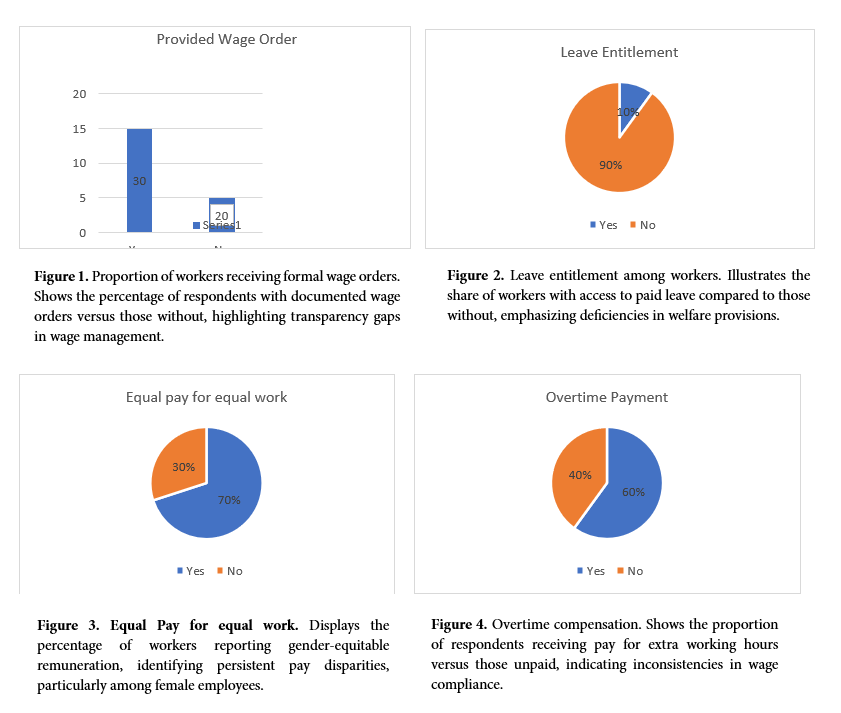

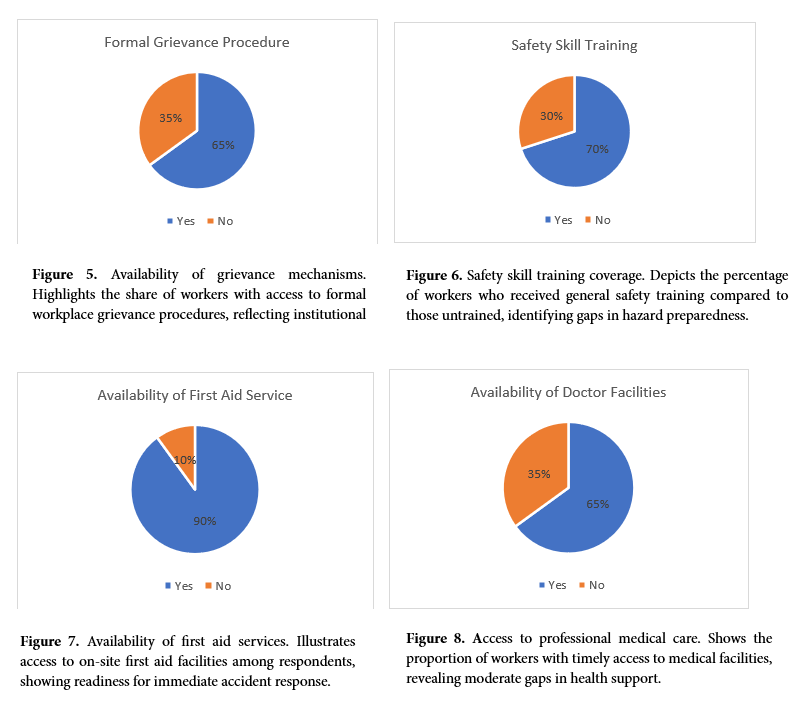

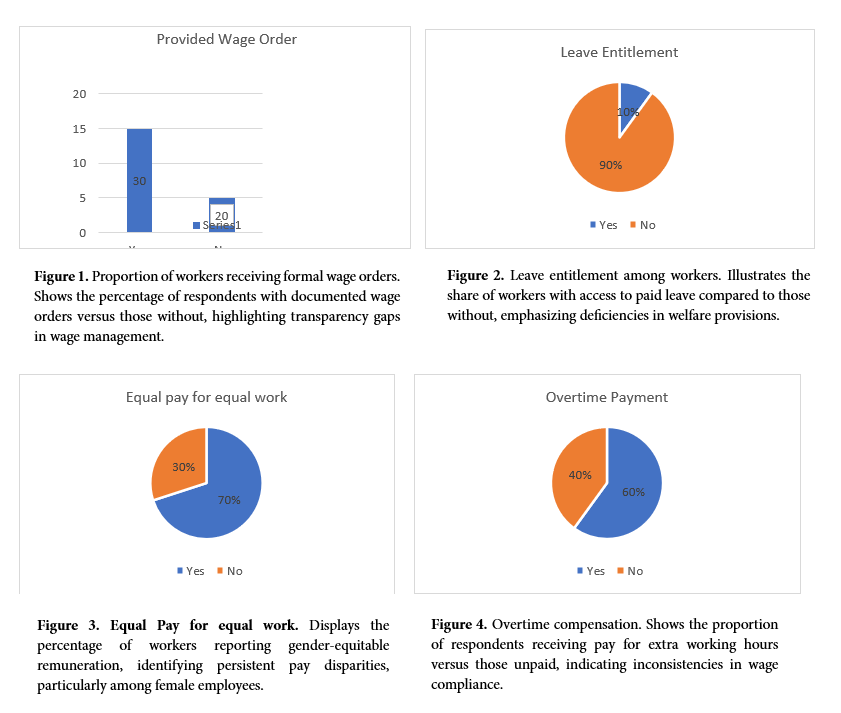

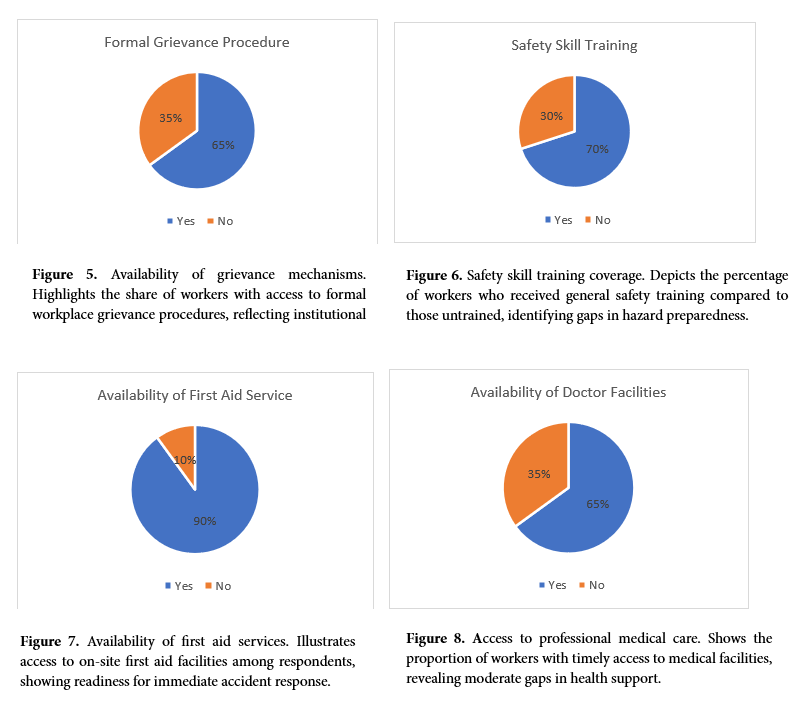

Ensuring equitable treatment and opportunities in the workplace is a cornerstone of labor rights, emphasized by the International Labour Organization (ILO) through conventions such as the Right to Organize and Collective Bargaining (Convention No. 98), Equal Remuneration (Convention No. 100), and the Protection of Wages (Convention No. 95). The survey results, presented in Figure 1–5, provide a nuanced picture of labor practices in Bangladesh. Regarding wage orders, 60% of respondents reported receiving formal wage documentation, while 40% did not (Figure 1). Wage orders are critical for transparency and safeguard workers from arbitrary wage deductions or delays. The absence of wage orders for a substantial portion of respondents indicates lapses in compliance with ILO Convention No. 95, highlighting the risk of informal or exploitative practices.

Leave entitlements emerged as a significant gap, with only 10% of respondents reporting access to leave and 90% lacking such benefits (Figure 2). This stark deficit contravenes both national labor laws and ILO Convention No. 132 on Holidays with Pay, which guarantees paid annual leave. The absence of leave benefits may contribute to overwork, stress, and decreased productivity, demonstrating an urgent need to address workers’ welfare comprehensively. Encouragingly, 70% of respondents reported receiving equal pay for equal work (Figure 3), aligning with ILO Convention No. 100. However, 30%—predominantly women—experienced pay inequities, highlighting persistent gender disparities and the need for stronger enforcement of equal remuneration policies.

Overtime pay, another key labor standard, was inconsistently applied. While 60% of respondents received compensation for extra hours, 40% did not (Figure 4). This inconsistency undermines fair labor practices as outlined in ILO Convention No. 1 on Hours of Work and indicates gaps in monitoring and enforcement. Similarly, access to grievance procedures, essential for addressing workplace conflicts, was reported by 65% of respondents, leaving 35% without formal mechanisms (Figure 5). The lack of grievance systems for a sizable proportion of workers suggests inadequate institutional support, emphasizing the need for broader implementation of conflict resolution structures.

Overall, the findings present a mixed scenario. Positive aspects include the provision of wage orders to a majority, the presence of grievance systems for many, and partial compliance with equal pay standards. Nonetheless, critical gaps persist, particularly regarding leave entitlement, overtime compensation, and gender wage equity. These shortcomings indicate that while labor laws exist on paper, their practical implementation remains uneven. Addressing these challenges through strengthened enforcement, gender-sensitive wage policies, expanded leave benefits, and broader access to grievance systems is crucial to achieving fair treatment for all workers.

3.2 Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Status

The study also assessed the status of Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) among workers, revealing both strengths and areas for improvement. Safety skill training was reported by 70% of respondents, leaving 30% without such preparation (Figure 6). This gap indicates that a substantial portion of workers may be ill-equipped to handle hazardous situations, underscoring the need for universal training programs. First aid availability, however, was high, with 90% of respondents confirming access (Figure 7). This reflects a robust preparedness for immediate medical needs, although universal coverage should be the goal. Access to professional medical care was reported by 65% of respondents, leaving 35% without adequate facilities (Figure 8), suggesting moderate gaps that could hinder timely treatment.

Alarmingly, only 20% of respondents reported the presence of proper security and preventive safety measures, whereas 80% lacked such protections (Figure 9). This highlights a critical vulnerability in proactive safety systems and indicates that most workplaces are reactive rather than preventive, increasing the risk of accidents and injuries. These findings suggest that while emergency response systems such as first aid are in place, preventive measures and structural safety enhancements require immediate attention.

3.3 Outcomes of OHS by Project Sites

A site-specific analysis of OHS outcomes across the Dhaka Elevated Expressway Project, MRT 6, and DCNUP projects reveals significant variation in safety practices. Regarding workers’ understanding of their health and safety responsibilities, Figure 10 indicates high awareness across all projects, with MRT 6 leading, followed closely by the Expressway Project. DCNUP, however, showed a comparatively higher proportion of respondents lacking awareness, pointing to potential communication or training gaps.

Safety discussions in the workplace, as shown in Figure 11, were generally frequent, with MRT 6 again showing the strongest performance. DCNUP lagged behind, suggesting a need for more structured discussions to reinforce safety culture. The use of Permit to Work (PTW) systems prior to tasks, illustrated in Figure 12, displayed stark differences. Both MRT 6 and the Expressway Project reported 100% compliance, reflecting strong procedural adherence. DCNUP, in contrast, showed a substantial shortfall, with nearly 80% of respondents indicating no PTW implementation, signaling a critical lapse in procedural safety.

Task-specific safety training, depicted in Figure 13, was notably insufficient across all sites. A majority of workers reported not receiving training tailored to their specific roles, with DCNUP performing the poorest, followed by MRT 6 and then the Expressway Project. Even where general safety awareness existed, the absence of task-specific preparation may elevate the risk of accidents, especially in high-hazard operations. These site-specific findings highlight uneven OHS practices, with some projects demonstrating robust compliance and others requiring urgent interventions.

In summary, the combined results underscore a complex reality. While there are encouraging indicators of worker awareness, first aid availability, and partial compliance with labor standards, persistent gaps in leave entitlement, gender wage equality, preventive safety measures, and task-specific training reveal systemic shortcomings. Economic disparities, modest housing conditions, and demographic characteristics further influence the vulnerabilities of workers. Addressing these gaps requires a multifaceted approach, integrating policy enforcement, worker education, gender-sensitive labor strategies, and investment in safe infrastructure. Strengthening both preventive and responsive OHS measures across project sites will not only improve workers’ well-being but also enhance productivity, morale, and the overall sustainability of labor practices in Bangladesh.