1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative force in drug discovery by improving predictive accuracy, accelerating molecular optimization, and enabling data-driven therapeutic development (Li et al., 2025). The integration of computational modeling, machine learning, and large-scale biological datasets allows researchers to analyze complex molecular interactions with unprecedented efficiency. Advances in computational biology, combined with increased availability of biological sequence, structural, and functional data, have enabled AI systems to identify patterns that were previously difficult or impossible to detect using traditional computational approaches (Wei et al., 2020; Xu, 2019). These advancements have positioned AI as both a decision-support tool and a hypothesis-generating system capable of accelerating drug discovery workflows.

Drug discovery is a complex and multistep process involving target identification, hit discovery, lead optimization, and preclinical and clinical validation. One of the major challenges in this process is understanding the relationship between molecular structure and biological function. Traditional computational approaches, such as sequence similarity searches and structural modeling, have provided valuable insights but often struggle with novel proteins or incomplete datasets (Pearson, 2013; Wang et al., 2016). Deep learning approaches have significantly improved the ability to model biological systems by extracting meaningful patterns from high-dimensional datasets and enabling more accurate prediction of protein structures and molecular interactions (Wei et al., 2020; Elnaggar et al., 2021; Rives et al., 2021).

Protein structure prediction represents one of the most important applications of AI in drug discovery. Accurate knowledge of protein structure is essential for understanding molecular mechanisms, identifying drug targets, and designing effective therapeutic compounds. Recent deep learning approaches have significantly improved the accuracy of protein structure prediction, enabling researchers to model protein folding and structural relationships with near-experimental precision (Varadi et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2020). These advances have dramatically expanded structural coverage of the proteome and provided valuable insights into protein function, interaction networks, and therapeutic target identification (UniProt Consortium, 2023; Wei et al., 2020). Structural databases and protein family resources further support functional annotation and drug target discovery by providing comprehensive molecular and structural information (Mistry et al., 2021; Sillitoe et al., 2019).

In addition to structural prediction, AI has significantly improved protein function prediction and biological annotation. Functional annotation is essential for understanding protein roles in biological pathways and disease mechanisms. The Gene Ontology provides a standardized framework for functional classification, enabling systematic annotation and analysis of protein function across species (Ashburner et al., 2000; The Gene Ontology Consortium, 2021). Deep learning–based methods have improved functional prediction accuracy by integrating sequence data, protein interaction networks, and ontology-based information (Kulmanov et al., 2018; Kulmanov & Hoehndorf, 2019; Cao & Shen, 2021; Fan et al., 2020; You et al., 2021). Multimodal deep learning approaches that combine sequence, structural, and network information further enhance predictive accuracy and enable more comprehensive functional characterization of proteins (Mao et al., 2025; Yu & Bar-Joseph, 2020; Gu et al., 2023; Jiao et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024).

Recent advances in neural network architectures have also contributed significantly to molecular representation and prediction. Attention-based models, originally developed for sequence analysis, have demonstrated strong performance in capturing long-range dependencies and structural relationships in biological data (Vaswani et al., 2017). These approaches enable improved prediction of molecular properties, functional interactions, and biological activity. Deep learning techniques can also integrate multiple data modalities, including sequence information, structural features, and interaction networks, to provide more accurate and biologically meaningful predictions (Rives et al., 2021; Zahran et al., 2021; Elnaggar et al., 2021).

AI has also contributed to improving biological databases and annotation resources, which are essential for drug discovery. Comprehensive protein knowledgebases and structural repositories provide valuable information for understanding molecular mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets (UniProt Consortium, 2023; Varadi et al., 2022). Ontology-based representations and vector-based embedding techniques enable efficient modeling of biological relationships and functional similarity, supporting improved prediction accuracy and knowledge discovery (Fatima et al., 2018; Smaili et al., 2019; Li et al., 2024). Community-driven benchmarking initiatives have further advanced the field by systematically evaluating protein function prediction methods and promoting experimental validation of computational annotations (Zhou et al., 2019).

Despite these advances, several challenges remain in applying AI to drug discovery. One major limitation is the variability and incompleteness of biological datasets, which can introduce bias and reduce model generalizability. Accurate prediction of protein function and biological processes remains challenging due to the complexity of molecular systems and limited experimental validation data (Zhou et al., 2019). Additionally, differences in model architectures, training procedures, and evaluation methods can affect reproducibility and make comparisons between studies difficult (Radivojac et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2016).

Another important challenge is ensuring accurate and reliable functional annotation of proteins. Although deep learning models have significantly improved prediction performance, continued integration of diverse biological data sources, including sequence, structural, and interaction data, is essential for further progress (Kulmanov & Hoehndorf, 2020; Li et al., 2022; Gu et al., 2023). Advances in protein family classification, structural annotation, and sequence analysis tools will continue to enhance AI-driven drug discovery and enable more accurate identification of therapeutic targets (Mistry et al., 2021; Pearson, 2013).

Overall, AI is reshaping drug discovery by enabling more accurate molecular prediction, accelerating therapeutic development, and improving understanding of biological systems. The integration of structural biology, computational modeling, and deep learning provides powerful tools for identifying new therapeutic targets and optimizing drug candidates. Continued advancements in AI methodologies, combined with expanding biological datasets and improved computational infrastructure, are expected to further enhance drug discovery efficiency and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

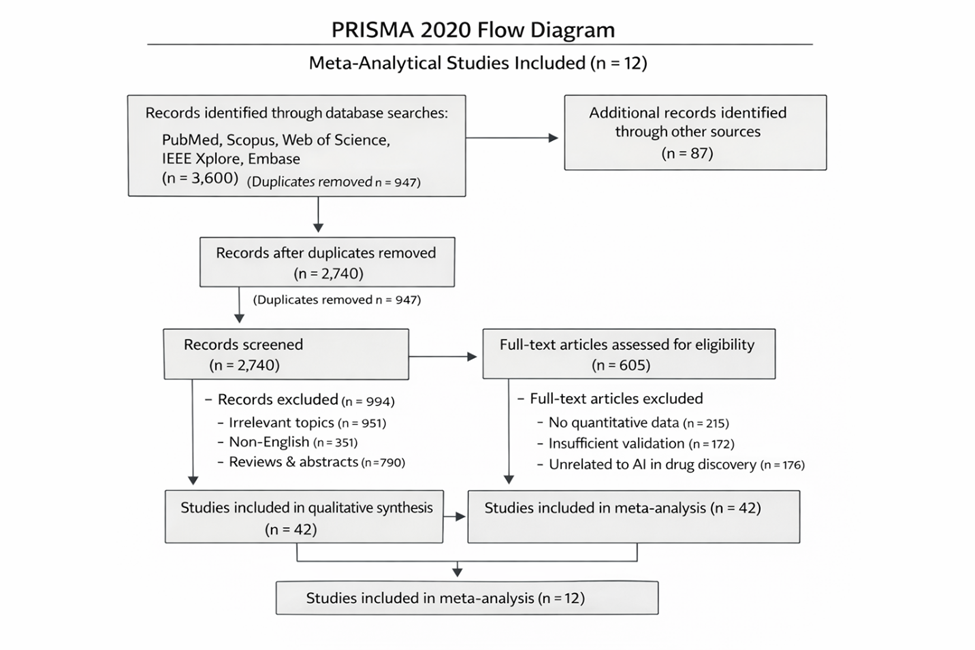

This taxonomical review and meta-analysis aim to synthesize current advances in AI-driven structural modeling, molecular prediction, and functional annotation. By evaluating diverse AI applications, including protein structure prediction, function prediction, and molecular interaction modeling, this review provides a comprehensive assessment of AI’s capabilities, limitations, and future potential in drug discovery.